American racing icon John Charles Seymour was the fearless champion, a young talent recruited onto Indian’s factory program alongside fellow legends like Gene Walker, Hammond Springs, Maldwyn Jones, and Eddie Brinck during the sport’s spectacular revival following WWI. During one of the most dynamic and exciting eras of the sport, Seymour acted as an anchor for the storied Springfield brand and remained one of the few men left at the top of the professional racing game by the late 1920s. Born in Schaffer, just outside Escanaba, in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, on October 8, 1898, to Canadian immigrants, Seymour tragically lost his mother and older brother in the summer of 1908 at only 10 years old. Unlike many at the time, he was able to maintain his schooling and took a job working on motorcycles at a local shop as a teenager. By the time of his graduation, Seymour had saved up enough to purchase his own Indian, a brand he would stick with for the next decade.

There are names spoken in reverence whenever early American motorcycling legends are recalled; Hedstrom, DeRosier, Ottaway, but etched just as indelibly into the books of our two-wheeled past is that of, Charles Bayly Franklin, the soft-spoken Irishman who defined what a motorcycle was to be for a new modern era and cast the mold for its future.

A Dubliner, innovator, racer, and genuine pioneering motorcycle icon, Franklin remains among the most significant contributors to motorcycling culture to have ever jockeyed a throttle. Long before he reshaped the fortunes of the Indian Motorcycle Company, Franklin was a rising star in Ireland’s young yet burgeoning motorcycling scene.

Albert "Shrimp" Burns, the young California crack that once pestered the country’s best riders, is perhaps one of America's most recognizable and widely loved stars from the early days of motorcycle racing. Growing up just around the corner from the local Pope dealer in Oakland, Burns was the scamp perpetually having to be shooed away from the motorcycles parked out front by management. It is said that his first ride was actually the result of the manager's absence, a brief window in which the boy fired up one of the machines and took off around the block. Coming of age in the sensational motordrome era, Shrimp soon developed an interest in the flourishing sport of racing. Still, unlike many of his schoolyard buddies, Shrimp wasn't content to simply sit and watch. So, at the age of 14, he rebuilt an Indian twin and began competing in dirt-track races, bound for his destiny as one of the greatest motorcycle racers in history.

It is strange to think that Harley-Davidson, the now global giant in the world of motorcycling, began its story without fanfare or celebration, a single flake amid the blizzard of motorcycle brands blanketing the country at the turn of the century. A genuine personification of the American dream, what would eventually become The Harley-Davidson Motor Company famously began in the imagination of two boyhood friends, neighbors Arthur Davidson and William S. Harley, who became enthralled with creating their own motorized cycle as soon as the technology arrived in the US. Undoubtedly inspired by machines from America’s earliest motorcycle builders like E. R. Thomas, as well as local upstarts like Mitchell and Merkel humming and popping on the streets of Milwaukee by 1901, the first evidence of the teenaged duo’s exploration dates to a schematic sketch William Harley made of a small engine in July 1901. Still, it wasn’t until the practical machining skills of Arthur’s experienced older brother, Walter, who returned to Milwaukee from his railroad job in Kansas for the eldest Davidson brother, William’s wedding in 1903, that the first complete and functional Harley-Davidson came together in a real way. Together, the trio spent the winter of 1903/1904 working out the kinks and gremlins discovered in that prototype in the Davidson family home’s back yard shed on shed to produce a more robust, production-ready motorcycle by the spring of 1904, with three more built by the end of the year.

Though not as recognizable as many of his iconic peers, Robert Thomas Stubbs, better known as Bob, was a champion pioneer in the earliest days of motorcycle sport at the turn of the century. Hailing from Birmingham, Alabama, Stubbs was the eldest of ten children of Lizzie Gilbert and Thomas Jefferson Stubbs, a Confederate soldier who fought in the battles of Tuscaloosa and Chickamauga. Like many of America's first motorcycle racers, Stubbs was active in the cycling world of the late 1800s, competing in regional events throughout the southeast. His passion for two-wheeled racing soon turned to the exciting new motorized machines as they first appeared in the South. As Indian was among the first manufacturers to establish a firm grip on production and distribution at scale, Stubbs' name became among the first in the American South, just as his counterpart in Georgia, Harry Glenn, to appear beside mentions of the Springfield marque in the earliest local competitions. By 1907, Stubbs had been elected President of the newly formed Birmingham Motorcycle Club, where he organized some of the first track competitions in the region at the nearby dirt track at the Alabama State Fairgrounds, arranging the first ever meet there on July 4, 1907, and sweeping every event.

The tail end of 1914 stirred talk throughout the motorcycling world of a new contender in the racing game, and with Harley-Davidson’s victories in Venice, Oklahoma City, and La Grande as the 1915 season began, the rumblings had been proven true. Still, it was at the 2nd annual Dodge City 300, the Coyote Classic held July 3rd, 1915, that the Motor Company staked its claim as the American motorcycle manufacturer to beat. All of the momentum built by the company over the previous decade and the effort put in by Bill Ottaway to create a world-class racing team the year before came to a crest in a small town in the heart of America as the eyes of the motoring world turned towards Kansas.

Seen here is the Harley-Davidson Motor Company in 1906, featuring founders, staff, and customers alongside a handful of its earliest machines. The photo is listed as 1906; however, it may actually be 1907, as it was taken in front of the Chestnut Street factory, the first expansion beyond the Davidson family's shed. This is because Chestnut St. wasn't complete until December 1906, so if this was taken then it looks unseasonably balmy.

Former bicycle racer and American motorcycle pioneer Walter G. Collins onboard his 1908 Indian twin in San Francisco, July 12, 1908. “Mile A Minute” Collins, as he became known after being the first to top the 60 MPH mark at LA's Agriculture Park track onboard a cumbersome French Peugeot twin, was one of the founding fathers of American motorcycle racing. Hailing from LA, Collins had been among the best bicycle racers on the West Coast during the sport’s heyday before quickly transitioning to motorcycles once they first arrived.

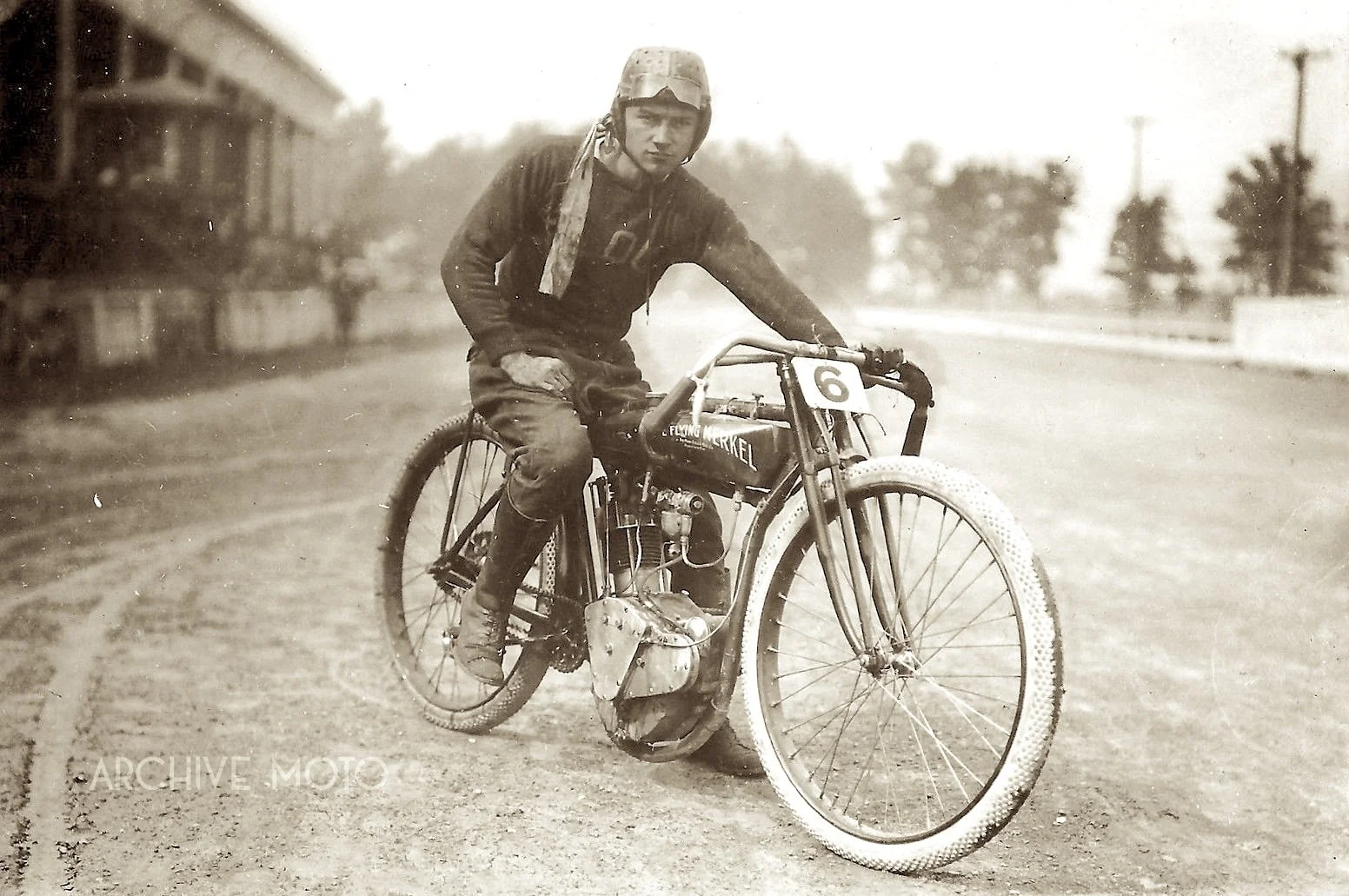

Among my favorite pioneer motorcycle racers and images, Cleo Francis Pineau embodied all that made that first generation of racers a class of their own. Here he is photographed sitting astride his single-cylinder Flying Merkel racer during the June 1914 races in Toledo, Ohio. Like so many of America's early professional motorcycle racers, Cleo Francis Pineau was carved from the rugged wood of the frontier—equal parts grit, speed, and insatiable wanderlust. Born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, during the waning years of the 19th century, Pineau was slight in both stature and temperament, coming of age at a time when machines were beginning to reshape the modern world. He never took kindly to being boxed in by schoolhouse walls. Legend has it he left formal education behind in the sixth grade—drawn not by books but by speed, fuel, and the open road.

On the warm autumn evening of October 21, 1912, beneath the arc lights of the Lake Cliff Motordrome in Dallas, Texas, a stadium full of racing enthusiasts witnessed a miracle on the boards. The country was still in shock as the tragedy at the Valisburg Motordrome occurred only weeks before, on September 8. The horrific and now infamous crash, the precursor of the “murderdrome” moniker, claimed the lives of Indian racing stars Johnny Albright and local Texan hero Eddie Hasha, along with 6 spectators, 5 of whom were teenage boys. In the weeks that followed the Valisburg track shutdown, papers nationwide ran stories about the carnage, and an outcry for improved safety standards prompted organizers and promoters to implement new rules and infrastructure. For the riders, however, racing was their livelihood, and though their friends had just perished, death was just another aspect of their daily lives and most were eager to get back onto the boards.