Home

Home

Welcome

Archive Moto is an ongoing research and publishing project dedicated to rediscovering America's rich history of motorcycle culture, one story at a time.

Recent Articles

Recent Articles

FEATURED VIDEO

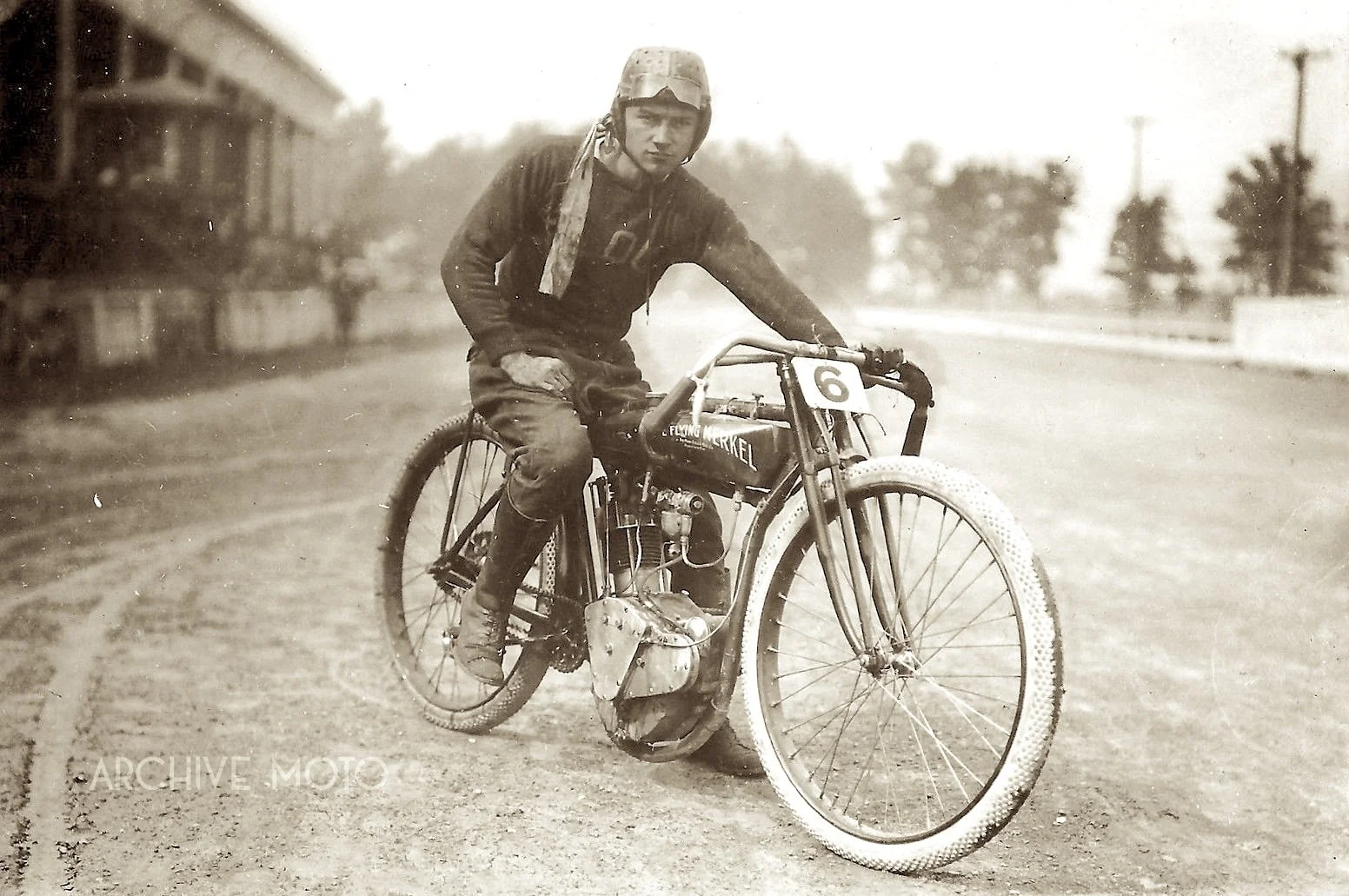

Among my favorite pioneer motorcycle racers and images, Cleo Francis Pineau embodied all that made that first generation of racers a class of their own. Here he is photographed sitting astride his single-cylinder Flying Merkel racer during the June 1914 races in Toledo, Ohio. Like so many of America's early professional motorcycle racers, Cleo Francis Pineau was carved from the rugged wood of the frontier—equal parts grit, speed, and insatiable wanderlust. Born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, during the waning years of the 19th century, Pineau was slight in both stature and temperament, coming of age at a time when machines were beginning to reshape the modern world. He never took kindly to being boxed in by schoolhouse walls. Legend has it he left formal education behind in the sixth grade—drawn not by books but by speed, fuel, and the open road.

Otto Walker and Leslie Parkhurst, two of history’s most accomplished pioneer motorcycle racers and pillars of Harley-Davidson legendary factory team, the Wrecking Crew, bombing the slant at New York’s Sheepshead Bay Speedway in July, 1917. The two men were on the hunt for speed records, specifically the 500-mile, 1,000-mile, and 24-hour records for solo riders and sidecars as organized by George Wood, the Motor Co.’s distributor in the state. Otto Walker was on hand as he had been working as a foeman in Harley’s Manhattan branch following the leg injury that took him out of the game in 1916. Eager to get back in the saddle but still nursing his injury, Walker signed up to run the sidecar for the 24-hour record attempt, with Carl Lutgens acting as copilot in the hack.

In the pantheon of American motorcycles, few names command the reverence of the Henderson brand. From its earliest rumblings in Detroit in 1912 to its final breath in 1931, Henderson was more than just a motorcycle—it was a refined symbol of engineering ambition and pre-Depression optimism. The company's signature inline four-cylinder engine didn't just set records; it emblemized the highest reaches of motorcycling life and defined one of its richest eras.

Beginning with brothers William and Tom Henderson, who, steeped in a legacy of mechanical innovation, set out at the turn of the 20th century to build the finest motorcycle in America. While Tom was the more business-oriented of the two and set out to handle the administrative aspects of their venture, the younger William was the creative force.

Herschel Chamberlain, a local amateur motorcycle racer from Detroit, Michigan, is but one of the countless hundreds of America’s daring, early enthusiasts to have found the thrill of speed on two wheels and took to the track to test their mettle. Proudly straddling his winning mount, Chamberlain rode this spartan and unruly 1911 Indian twin to victory in the 3-mile novice competition at the Detroit Motorcycle Club’s Labor Day weekend races that same year. The young speedster rolled to the line alongside some of the finest riders in the country, men like Frank Hart, Johnny Constant, Don Klark, Charles Gustafson, and William Teubner.

Los Angeles' own J. Howard Shafer, one among the few pioneers of motorcycle racing in America with his Thor twin in 1908. Shafer was a part of the first class of enthusiasts in the Los Angeles area at the turn of the 20th century and one of the first motorcyclists in the country to venture into competition. As a founding member of the Los Angeles Motorcycle Club, Shafer acted as the club's secretary and was highly active within an elite group, including racing icons like Paul Derkum, Charlie Balke, Ray Seymour, Will Risden, and Morty Graves, many of which represented the first motorcycle dealerships in California. Before long, the club began sponsoring and promoting races at the nearby 1-mile-long horse track at Agriculture Park.

I have had the distinct pleasure of being asked to give a guest lecture at the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum this Thursday, February 27 at 7 pm EST, available for anyone to attend for free via Zoom.

Curtiss was one among America’s first class of motorcycle pioneers, equal parts engineer, entrepreneur, and fearless sportsman that helped give birth to the machines themselves. Often overlooked given his diverse mechanical interests and successes in the earliest days of aviation, Curtiss stood alongside men like Charles Metz, Oscar Hedstrom, and Joseph Merkel as the founding fathers of both the American motorcycle and the sport of motorcycle racing. Join in tomorrow, February 27 at 7 pm EST for a look back to the beginning of motorcycle racing and the invaluable contributions made to the culture by Hammondsport’s own Glenn Curtiss.

I’m looking into re-releasing my first book, Georgia Motorcycle History soon. It was a project which marked the beginning of my interest in writing about this unique history back in 2013 which was funded with the support of the community. Though it was a narrow niche the response was inspiring, and after 3 pressings sold to enthusiasts in over 20 countries I fell in love with researching motorcycle history and decied I wanted to do what I could to help preserve stories from the early days of this rich culture of ours. The project quickly evolved into Archive Moto, and I have thuroughly enjoyed the ooportunity to dig deeper into my passion, connect and collaborate with so many like-minded folks, and share in this collective interest. GMH has been sold out for the better part of 5 years now, and though the printing house in Georgia I used to produce it is no longer available, I have been exploring ways to have another pressing.

Indian’s Big Base 8-valve was the very concept of speed, raw and uncompromising, distilled by one of the most talented engineering pioneers specifically for the task at being unbeatable yet refined in its simplicity as only Oscar Hedstrom could accomplish. And for that, the Big Base remains a legendary machine, equal parts brutality and elegance, the embodiment of the thrilling age of the board track motordrome, … and in a word, a purebred.

In early September 1910, Ray Seymour returned home to California as one of the world's top motorcycle racers. He was the newest recruit on Indian's dominant factory team as an understudy of the undisputed greatest motorcycle racer in the world, Jacob DeRosier. Only four years prior, Seymour had thrown his leg over a motorcycle for a race at LA's Agriculture Park for the first time, but in 1910, he returned with the crown of National Amateur Champion resting on top of his dusty blonde hair. He reacquainted himself with California's warm winter climate with a few dirt track races in San Jose before returning to Los Angeles. Once home in LA in late September, Seymour and his Indian cohorts soon gathered to assault the records at the large 1-mile wooden circle at Playa Del Rey.

GRIT - A History of Board Track Racing

A three-part documentary examining the history of the American Motordrome.

Often conflated with carnival thrill shows and the massive wooden speedways of the 1920s, America's original timber race tracks, called motordromes, were dangerous and exhilarating saucers where the toughest of the tough went elbow to elbow for a taste of the glory and the gold. For just 5 short years between 1909 and 1914, only 26 of these perilous stadiums were ever built, many having only hosted motorcycle races for a season or two. Still, inside their steeply banked walls, the heroes of a thrilling and often deadly sport captivated the country, cementing a legacy and mythology which continues to sends chills through those that learn about it.

Head to the Archive Moto Youtube Channel to watch the trailer for GRIT, a three part documentary series looking at the history board track racing, one of America’s most infamous and sensational sports.

Georgia Motorcycle History

Georgia Motorcycle History

GEORGIA MOTORCYCLE HISTORY

The First 60 Years 1899-1959

This stunning 270 page, cloth-bound, hardcover coffee table book illuminates the earliest days of American motorcycling culture through the photographs and stories of Georgia.

Among my favorite pioneer motorcycle racers and images, Cleo Francis Pineau embodied all that made that first generation of racers a class of their own. Here he is photographed sitting astride his single-cylinder Flying Merkel racer during the June 1914 races in Toledo, Ohio. Like so many of America's early professional motorcycle racers, Cleo Francis Pineau was carved from the rugged wood of the frontier—equal parts grit, speed, and insatiable wanderlust. Born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, during the waning years of the 19th century, Pineau was slight in both stature and temperament, coming of age at a time when machines were beginning to reshape the modern world. He never took kindly to being boxed in by schoolhouse walls. Legend has it he left formal education behind in the sixth grade—drawn not by books but by speed, fuel, and the open road.