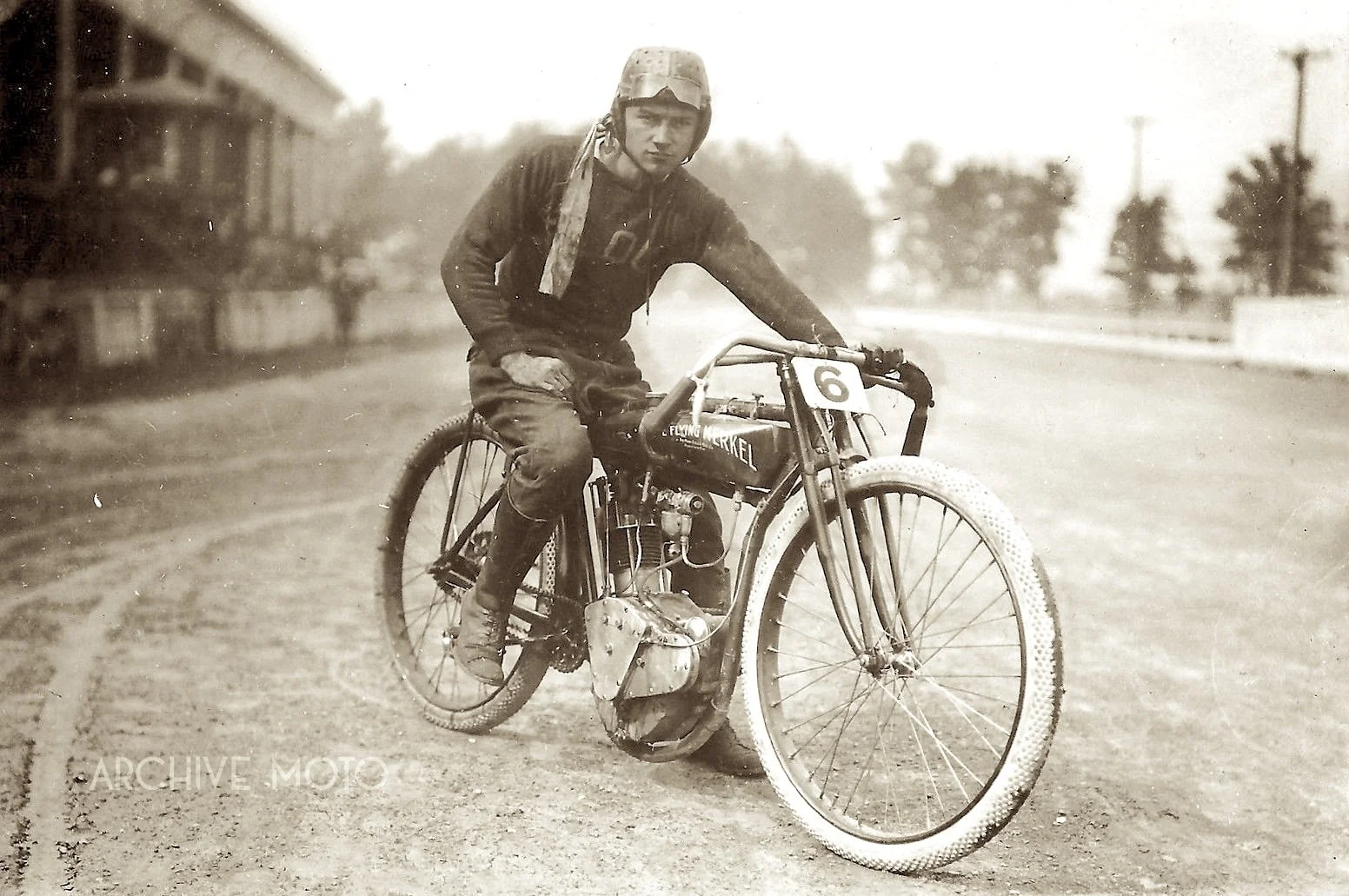

Among my favorite pioneer motorcycle racers and images, Cleo Francis Pineau embodied all that made that first generation of racers a class of their own. Here he is photographed sitting astride his single-cylinder Flying Merkel racer during the June 1914 races in Toledo, Ohio.

Like so many of America's early professional motorcycle racers, Cleo Francis Pineau was carved from the rugged wood of the frontier—equal parts grit, speed, and insatiable wanderlust. Born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, during the waning years of the 19th century, Pineau was slight in both stature and temperament, coming of age at a time when machines were beginning to reshape the modern world. He never took kindly to being boxed in by schoolhouse walls. Legend has it he left formal education behind in the sixth grade—drawn not by books but by speed, fuel, and the open road.

A wall rider in the early Wall of Death thrill shows performed along the Vaudeville circuit, Pineau rode both Indian and Merkel machines in his days on the walls.

Pineau began his love affair with two-wheels as a wall rider on the Vaudeville circuit in 1911, but by his late teens, Pineau had already established himself as a fixture on the national racing circuit, riding for the famed Flying Merkel factory team. To be a Merkel man in those days was to ride in rare company—alongside men like Lee Taylor, Ralph DePalma, Charlie Balke, and Maldwyn Jones, all giants in the infancy of American motorsport. Merkel's distinctive orange machines, built by the Merkel-Light Motorcycle Company of Pottstown, Pennsylvania, were among the most advanced motorcycles of the day, famed for their "spring frame" rear suspension and precision engineering. Pineau took to them naturally, covering thousands of miles on perilous board track motordromes and dusty county fairground tracks alike as he carved out his legend.

Three legendary pioneers of American motorcycle racing, Maldwyn Jones, Cleo Pineau, and Lee Taylor on the line for the 100-mile National held in Toledo, OH on June 9th, 1914. The three made up the infamous Yellow Jackets, Flying Merkel's factory racing team that were consistently among the top contenders of the early teens.

Maldwyn Jones and Cleo Pineau, two prolific pioneer American motorcycle racers prepped and ready to charge the the sandy roads of Savannah, GA for the 1913 American Classic 300-Mile Road Race.

Pineau at the Miami Cycle & Manufacturing Co., makers of Flying Merkel motorcycles after a 1,102 miles trip on May 30, 1916.

He was a regular presence at the major races of the early 1910s, from the roaring boards of Los Angeles and Chicago to the grueling long-distance contests of the Southeast. In both 1913 and 1914, Pineau competed in the prestigious Savannah 300, a punishing 300-mile endurance race through the mossy lowlands of Georgia. There, he faced off against the best riders of the era, including his teammate Lee Taylor, who bested the field on both occasions. Still, Pineau's steady hand and steely composure made him a perennial contender, and his reputation only grew with each season.

Then came the Great War and, with it, the suspension of professional racing. But for Pineau, the call to serve wasn't just a patriotic impulse—it was another challenge to conquer. Unwilling to wait for the United States to officially declare war on Germany, much less settle for duty in the infantry. He first attempted to enlist in his family’s homeland of France, but was denied given his lack of French citizenship. Undeterred, he then crossed the border and enlisted with Canada’s Royal Flying Corps by way of Toronto in December 1917, later integrated into the newly created Royal Air Force. If straddling a race-tuned V-twin at 90 mph required courage, flying a canvas-and-wire biplane into a dogfight over the Western Front demanded something closer to madness. Pineau, of course, thrived in the skies and played down the inherent risks involved in a letter written to his mother to inform her of his enlistment, Pineau is quoted as stating “Flying is so much less dangerous than motorcycle racing. In fact there is no danger in it at all. I will get a good commission.” Pineau cut his teeth on the Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” and the stubby Avro biplane before shipping out from Halifax to England with little more than wide eyes and a pilot’s ambition. Once across the Atlantic, Pineau trained in the legendary Sopwith Pup and its more muscular successor, the Camel — a fighter that demanded respect and punished hesitation. Over four months and 87 logged flight hours, he transformed from a desert-bred daredevil into a fully fledged combat pilot.

A certified Flying Ace in WWI, Cleo was among the elite few pioneer aviators to earn Britain’s Distinguished Flying Cross.

France came next — and with it, No. 210 Squadron of the newly christened Royal Air Force. There, Pineau earned assignment to Hangar No. 1, the elite echelon of the War Birds — a rarefied group within the RAF that marked its members not just by skill, but by their sheer tenacity under fire. His instincts as a racer—quick thinking, spatial awareness, and nerves of ice—translated seamlessly to aerial combat. Flying over the blood-soaked fields of France in the notoriously unstable yet ferociously nimble Sopwith Camel, Pineau tore through the skies with purpose. In a flurry of engagements over the Western Front, he shot down four of Germany’s formidable Fokker D.VIIs and drove down two more, earning the coveted status of flying ace — a title worn lightly by those who survived long enough to claim it.

But fate in the skies was fickle. Not long after his sixth confirmed victory, Pineau found himself on the wrong end of a dogfight near Roulers. A Fokker Triplane got the better of him, and his Camel was torn from the heavens. He survived the crash but fell into German hands, spending the final two months of the war behind barbed wire in a prison camp reputedly overseen by the son of Kaiser Wilhelm himself. It was a far cry from the clouds, but Pineau endured, a flier to the core — restless, unbroken, and waiting for the sky to call him back. When the war ended, Pineau returned home a hero. He bore the scars of battle but also the glint of decorated valor. England, France, and Belgium all honored his service with medals, and King George V himself sent a handwritten letter welcoming his return—a rare gesture that spoke volumes about Pineau's exploits abroad. “The Queen joins me in welcoming you on your release from the miseries and hardships which you have endured with so much patience and courage,” the King wrote. “During these many months of trial, the early rescue of our gallant officers and men from the cruelties of their captivity has been uppermost in our thoughts.” For his heroism in France, Pineau was awarded Britain’s Distinguished Flying Cross.

A 1918 Sopwith Camel F-1

But just as the war had changed the world, it had altered Cleo as well. Though he returned to racing for a spell, he began to shift gears toward industry and innovation. In the late 1920s, he founded the Radiant Steel Products Company, which would go on to manufacture a wide array of industrial components. Remarkably, the company still operates today, a testament to Pineau's vision and determination, extending beyond the racecourse. Not content to merely build steel, Pineau turned his attention back to the skies. He played a leading role in the creation of the Williamsport-Lycoming Airport in Pennsylvania, a project that reflected his enduring passion for aviation. At its dedication, two of America's most storied aviators—Wiley Post and Amelia Earhart—stood beside him. It was a moment that bridged the noisy chaos of prewar board tracks with the brave new world of commercial flight.

In this iconic photograph at the top of this article, a 20-year-old Cleo Pineau sits astride his single-cylinder Merkel racer during the June 1914 races in Toledo, Ohio. Clad in riding leathers and gazing dead ahead, his expression is one of focused defiance—the kind worn only by men who knew full well the risks waiting at the next turn. His teammate Lee Taylor would take the win that day and later repeat the feat in Savannah aboard an Indian twin, but Pineau's presence in the lineup spoke to his stature in the sport. He was not just a participant—he was a symbol of its restless, fearless spirit. In the long shadow of motorsport history, it's easy to overlook men like Cleo Pineau—those who straddled two worlds, prewar and post, racer and soldier, innovator and adventurer. But his story, like the hum of a Merkel twin on a wooden oval or the whine of a biplane engine over France, deserves to be remembered.