Johnny Seymour talking shop with Indian veteran and head of the experimental racing department Charles Gustafson Jr. on the beach Daytona for Seymour’s record-breaking runs in early January 1926.

John Charles Seymour

American racing icon John Charles Seymour was the fearless champion, a young talent recruited onto Indian’s factory program alongside fellow legends like Gene Walker, Hammond Springs, Maldwyn Jones, and Eddie Brinck during the sport’s spectacular revival following WWI. During one of the most dynamic and exciting eras of the sport, Seymour acted as an anchor for the storied Springfield brand and remained one of the few men left at the top of the professional racing game by the late 1920s. Born in Schaffer, just outside Escanaba, in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, on October 8, 1898, to Canadian immigrants, Seymour tragically lost his mother and older brother in the summer of 1908 at only 10 years old. Unlike many at the time, he was able to maintain his schooling and took a job working on motorcycles at a local shop as a teenager. By the time of his graduation, Seymour had saved up enough to purchase his own Indian, a brand he would stick with for the next decade.

Gritty and ambitious, young Seymour began pushing his stock Indian around the fairground horse track, and in January 1916, he was entering and winning his first races. By the end of that same year, the 17-year-old Seymour had earned a reputation as the best racer in the area, but as the war in Europe interrupted life in all facets of American life, Johnny’s ascent in the sport was halted. Though the initial U.S. Selective Service Act applied only to men 21-30, Seymour, then 19, submitted his draft card in June 1918. Naturally, Seymour, known as the local “speed demon,” was tapped by Uncle Sam to the full extent of his riding skills, and records indicate he served as a motorcycle-mounted military police in the U.S. Army from August to December 1918. Upon his release, Johnny Seymour again took to the saddle, eagerly awaiting the return of sanctioned competition.

Pioneer motordrome star turned Indian racing manager Erle “Red” Armstrong with his 8-Valve at the 1916 Dodge City.

Many veteran professionals were still making their way back home from Europe at the start of 1919, so as the big factories rebooted their racing programs, those riders who were ready began traveling to any events available, including half-mile dirt-track races and state fair races. Bill Ottaway, head of the factory effort at Harley-Davidson, was quick to begin reassembling his stable of talent and sent two of his best recruits, Albert “Shrimp” Burns and Ralph Hepburn, to Escanaba to run in the local half-mile races. When they arrived in Michigan’s U.P., Seymour was the man to beat. On July 21st, 1919, local hero Johnny Seymour put on a clinic for the crowd, giving the Motor Company’s finest a hard run for their money. Of the five races run from 1 to 5 miles, Seymour fought his way onto the podium in every event, even besting the two Harley factory riders in two events. In the post-war scramble to sign fresh talent, Seymour had officially hit the radar in Springfield and was recruited by Indian team manager and board track Motordrome pioneer Erle “Red” Armstrong. For the remainder of his two-wheeled career, Johnny Seymour would be an Indian factory racer joining Springfield legends like Gene Walker, Floyd Clymer, Curley Fredericks, Shrimp Burns, and Jim Davis.

He kicked off the 1920 season racing for the Wig-Wam out west, first in Greeley, Colorado, with new teammates Gene Walker, Shrimp Burns, and Floyd Clymer, locking in a 4th place finish in the 3-mile event. From there, he continued to consistently bring in podium after podium in Grand Junction, Fort Collins, Casper, Wyoming, Woodland, Kansas, and back to Denver for the Rocky Mountain Championship. Team boss Red Armstrong went on record to say that both Seymour and Burns were cut from the same cloth and were easily the two future stars of the Indian camp. By August, Seymour returned home to Escanaba for the first time since turning pro and closed out all five events. After racing for only 4 years, two of which had been interrupted by the war, Johnny Seymour was a hero of the U.P. and a rapidly rising star on the national scene.

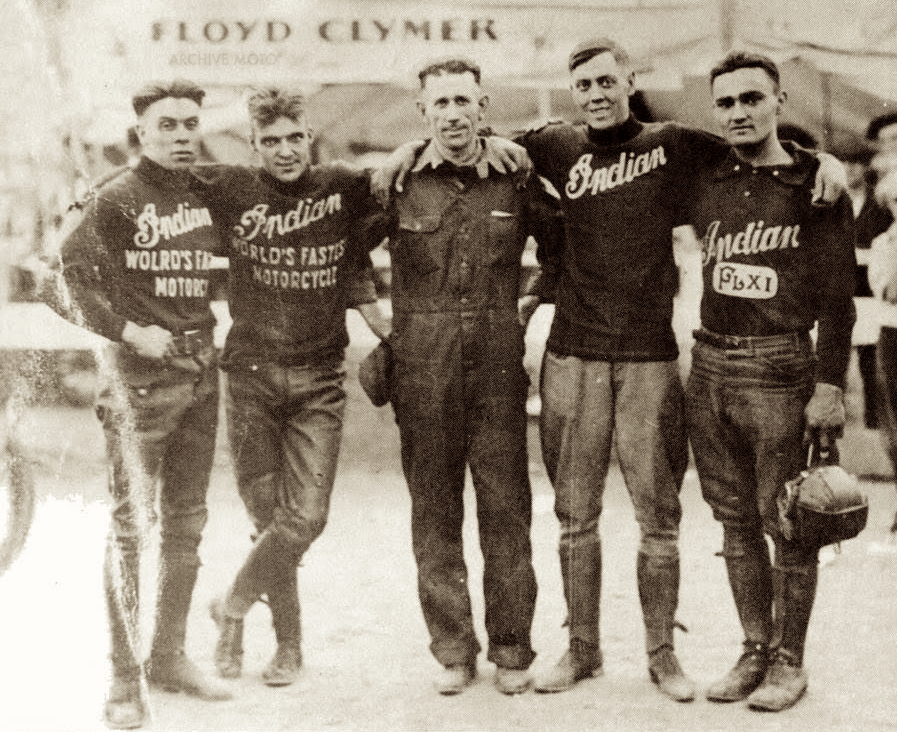

Seymour (far left) with the Indian factory team at the 300-Mile Dodge City race in 1921. L to R are John Seymour, Hammond Springs, Shrimp Burns, Curly Fredericks, Floyd Dryer, and Don Pope.

Seymour, Burns, Armstrong, Clymer, and Dryer, Dodge City, 1921.

He then relocated to Springfield, Massachusetts, as one of Indian’s most promising riders, crisscrossing the country and specializing in flat-track events on both singles and twins. He kicked off the 1921 season in Dallas with multiple wins and new records set for 1, 5, 8, and 10-mile distances, followed by still more victories in Colorado, Wyoming, and Kansas. By the time of the big 300-mile Dodge City race, Seymour had proven himself ready to run with the national icons of the day at what would be the final year of the historic, and uniquely American race. Despite being up against Harley-Davidson’s legendary Ralph Hepburn and his beastly 8-Valve Banjo Two Cam factory mount, Seymour gave a performance that justified his place on Indian’s team. Hepburn was unstoppable in 1921, ultimately winning 33 M&ATA races, with Dodge City his crowning achievement. At Dodge City, Hep led the race from the start, save for three laps when he stopped for fuel, and set new records for the 100-, 200-, and 300-mile distances. Still, though Ralph Hepburn was an unstoppable force in 1921, nipping at his rear tire in Dodge City was Johnny Seymour, who placed second in the prestigious race.

Albert “Shrimp” Burns onboard his 8-Valve factory special on the rooftop of the Springfield factory.

Tragically, just one month later, on August 14, Seymour’s teammate Shrimp Burns lost his life at the Fort Miami mile in Toledo, Ohio, following a collision with Eddie Brinck. Such was the nature of the sport in its golden era. Burns himself had just turned 23 and was riding an Indian with the same 8-Valve V-twin that the iconic Charlie Balke died on at Chicago’s Hawthorne flat track in 1914, just days before his 23rd birthday. Still, Seymour was a professional, and despite the dangers of the sport having hit so close to home with the loss of his teammate, there were still races to run. Two weeks later, Seymour was in Montreal and won two of the 3-mile events, followed by another win in Wichita to cap off the season. In 1922, the sport found itself in a dramatic decline compared to the years that bookended WWI. Following the death of Bob Perry, Ignaz Schwinn had all but terminated Excelsior’s racing efforts. Grappling with the high cost of R&D and the rising public distaste for Big Twin factory works racing, Harley-Davidson significantly pulled back its factory program, causing many of its top stars to either retire or find a new factory. Indian, then, remained the only of the Big Three in America still interested in racing. In February 1923, Seymour found himself teammates with his friend and former rival Ralph Hepburn following Gene Walker’s termination. Walker had protested running at Dodge City, given the conditions, which led to his contract being terminated and allowed Hep to become Indian’s top rider in 1922 and 1923.

Seymour and his Power Plus racer at the inaugural motorcycle events at the Altoona Speedway, September, 1923..

Seymour, however, continued to prove that he was among the most reliable racers, keeping tightly behind such a prodigious veteran of the sport as Hepburn. At Funk’s Motor Speedway in Winchester, Indiana, Seymour won every event he entered, managing to set a new world record for the mile on July 22nd. Still, 1924 brought still more atrophy, tragedy, and diversity to the sport as riders continued seeking out steady factory support and the newly formed AMA looked for ways to reinvigorate competition. Eugene Walker returned to Indian after his year-long stint at Harley-Davidson, while Springfield’s ringer Ralph Hepburn returned to the small group that Harley-Davidson was still supporting. Though the occasional big board track speedway event would occur, the small dirt ovals became the centerpiece of track racing in America. However, the V-twins of the day were consistently proving to be far too unwieldy for such venues. On April 13, 1924, at Los Angeles’ Ascot Park flat track, Harley’s Ray Weishaar and Indian’s Gene Walker were neck and neck at the front of the pack when Seymour rode the draft to shoot past the pair. As Seymour passed, Weishaar’s machine was sent into a violent speed wobble, sending the legendary racing veteran careening into the fence. Weishaar, like Burns and Perry, became the latest to give his life to the sport, but he wouldn’t be the last in 1924. Just two months later, on June 7th, while running test laps on the flat track in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, Eugene Walker collided with a tractor that had unknowingly pulled onto the track, marking yet another icon’s name in death’s ledger. In an effort to curb tragedies, the AMA would create three new, smaller displacement classes for 21 CI, 30.50 CI, and 45 CI the following season. The change would work to push the Big Three manufacturers to produce new lightweight and middleweight production machines like Excelsior’s Super X, Indian’s legendary Scout, and Harley-Davidson’s Models A and B Singles. Each would then go on to create a new generation of factory racing specials, OHV racers, and one-off speed machines that better fit within the confines of the country’s countless dirt ovals.

Paul Anderson hitting 135.71 MPH in Arpajon, France, 1925 onboard a 8-Valve Indian.

As for racing following the tragic end of two of the sport’s greatest in 1924, Seymour decided to switch it up and, in September, packed his bags for an Australian adventure, writing on his passport application “motorcycle racing” on the line labeled “Object of Visit.” He then set sail for Australia with fellow Indian teammate Paul Anderson and two of their Milwaukee “rivals,” Ralph Hepburn and Jim Davis. Hep had recently gotten married to fellow racer Fred Ludlow’s sister, Jo Ann, and was going on the trip as a part of their honeymoon. The quartet of American professionals arrived in Melbourne just in time for the much-anticipated opening of the Melbourne Motordrome, a banked concrete stadium designed by the father of the famed American Motordrome, Jack Prince. Unfortunately, Seymour took a heavy spill on the track during one of the races, severely breaking one of his legs, and was taken out of the remainder of the Australian tour. However, his traveling mates did quite well, running races all around Australia, including record-setting runs by Paul Anderson at Sellick’s Beach on a newly developed overhead-valve Indian twin. Anderson would continue his international career in Europe in 1925, where, at Arpajon, France, in October, he set still better speed records on board the OHV twin. However, due to timing inaccuracies, the speed records were not upheld.

Smokin’ Joe Petrali in his impromptu Harley-Davidson debut, Altoona, 1925.

Ralph Hepburn, Eddie Brinck, and Jim Davis onboard their factory Two Cam racers at Altoona, July 4, 1925.

Upon their return to the United States in May 1925, all but Seymour rejoined the action. With Seymour still on the mend, Indian recruited a new young rider named Joe Petrali to race at the big AMA 100-Mile Championship races being held at the Altoona board track speedway. In what could be described as a monumental blunder, Indian sent the machine Petrali was supposed to run at Altoona to Pittsburgh. Without a ride, a Petrali was forced to take in the race from the sidelines until Ralph Hepburn took a spill and injured his wrist. The story goes that Hep approached Petrali and worked out a deal. If Petrali could fix up Hepburn’s damaged machine, he could run it if he agreed to split his winnings. Not only did he win the 100-mile race, but Petrali also set an unbroken board track record of 100.36 mph. As decided, the money was split, and Petrali held his head high as he returned to his job in Kansas City at Al Crocker’s shop, the founder of Crocker Motorcycles. Harley tracked down Petrali, the lightning bolt of a 21-year-old, and quickly signed him to a contract.

The race in Altoona also marked Ralph Hepburn's departure from motorcycle competition to pursue his interest in auto racing. For the remainder of the 1925 season, Petrali and Jim Davis dominated the Big Twin events, but as soon as he was able, Seymour threw his hat back into the ring. By September, Seymour had returned and, at the AMA National Championships in Syracuse, New York, broke all records from 1 to 25 miles, followed by wins in the 3-, 5-, 10-, and 20-mile races in Allentown a week later. In Leadville, Massachusetts, on October 12th, Seymour helped usher in the AMA’s new 21 CI class with wins in the five and 10-mile events. His success, in part, was due to a new breed of OHV singles and twins developed in the experimental racing department at Indian, led by Charles Gustafson Jr.

Gustafson was Springfield royalty, having been as good as born into the company through his father’s early relationship with Indian and its Co-founder Carl Oscar Hedstrom during the company's birth. Gustafson Sr. was instrumental in several engineering advancements, most notably the development of the side-valve platform while working for Reading-Standard in 1907, which he later brought to indian in the form of 1916’s Power Plus after taking over for Hedstrom as Chief Engineer. The power Plus played a critical role in Indian's racing success from 1916 well into the 1930s, also providing a platform for Charles Franklin to develop Indian’s famed Scout and Chief models. Gustafson Jr. worked alongside his father at the company early on and raced alongside pioneers of the sport, including Arthur Chapple, Jacob DeRosier, Ray Seymour, and Charlie Balke. When a fellow founding father at Indian, Charles Spencer, left the experimental department in 1924, it was Gustafson Jr. who picked up the reins during a frenzied point in engine development in Springfield. With Gustafson’s brilliant management and novel racing designs, Johnny Seymour returned to the track in 1925 healed and ready to win. Johnny Seymour had only been able to race for half of the season, but by the end of 1925, he added more than two dozen victories and more records to his resume, including 3 National Championship titles and new records from 1 to 25 miles.

Back in Springfield for the winter, Gustafson and Seymour cooked up a plan to attack the standing speed records last set by the late Eugene Walker, who put the high numbers on the board for motorcycle land speed records back in April 1920, in the early days of Seymour’s career. Walker had stepped onto the Daytona sands in 1920 and stripped the new top-speed records set by the boys at Harley-Davidson just two months before (a video of which can be seen on the Archive Moto YouTube Channel), setting new records of 104 mph and 115.79 mph, records that remained in 1926. So, on January 11th and 12th, onboard the 61 CI, 8-valve machine seen in the primary photograph, as well as a 4-valve 30.50 CI single, Seymour obliterated Walker’s standing records by hitting an astonishing 132 mph onboard the twin, and 112.63 mph onboard the single. With Seymour on the throttle, Indian had set yet another speed record on the sands of Daytona, a tradition that dated back 23 years to the very founding of the company, when Oscar Hedstrom hit 53 mph on one of his first machines back in 1903. It had been 10 years since the high school boy from Escanaba began racing around his local horse track, and now Seymour was an internationally renowned motorcycle champion; he was the fastest man on two wheels. Seymour continued to compete in 1926, setting a handful of new records of his own, including on board a new AMA class of 21.35 CI, which he helped introduce the year before, and was on the scoreboard alongside teammate Jim Davis’s record-breaking run at Altoona and Curley Fredericks’ highest ever board track mark of 120.3 mph at Rockingham.

Johnny Seymour on an experimental 500cc OHV Indian single on which he hit a record speed of 112.6 MPH on January, 1926, Daytona Beach, Florida.

Seymour and mechanic Frank Hinckley in the #33 Streamline Miller at Indianapolis, 1934.

But the writing was on the wall; motorcycle competition and factory support were quickly deteriorating in the mid-to-late 1920s. The number of Class A factory track riders could be counted on two hands, and the once lucrative proposition of risking it all began to waver, at least in motorcycling. During that period, the time between the great board track days and the rise of Class C in the mid-1930s, several factors, including rising production costs and the onset of the Great Depression, led to reduced investment and sponsorship in motorcycle racing. At the same time, technological advances and public interest in auto racing contributed to its burgeoning popularity, drawing both fans and financial backing away from motorcycles. As a result, many racers, like Seymour and Ralph Hepburn before him, shifted their efforts to automobile racing. Between 1928 and 1936, Johnny Seymour redirected his fierce and fearless competitive drive into auto racing. Though he qualified and raced six times at the prestigious Indianapolis 500, mechanical failures plagued his four-wheel career, and he was never able to complete a single attempt at Indy. On May 20th, 1939, Seymour lost control of his rear-engined Miller at Indy, hitting the wall at speed. His car burst into flames, and Seymour was severely burned, though he survived. Finally, after a quarter-century of competition, dozens of speed records and countless championship victories, the 40-year-old speedster was ready to put up his leathers for good. John Charles Seymour settled in Detroit with his wife, Marie, and their two daughters, Joan, Cheryl, and Jancarla, where he managed the Belle Isle Saddle Club until he passed away at 61 on February 26, 1958. John Charles Seymour’s career stands as a measure of an era when courage, skill, and endurance defined greatness, and his legacy endures not only in records and victories, but as a formative figure whose influence helped shape the very foundations of American motorsport.

American racing icon, John Charles Seymour, 1930.

A special thanks to the Glenn family for allowing me to share the stunning main photograph from Harry’s collection.