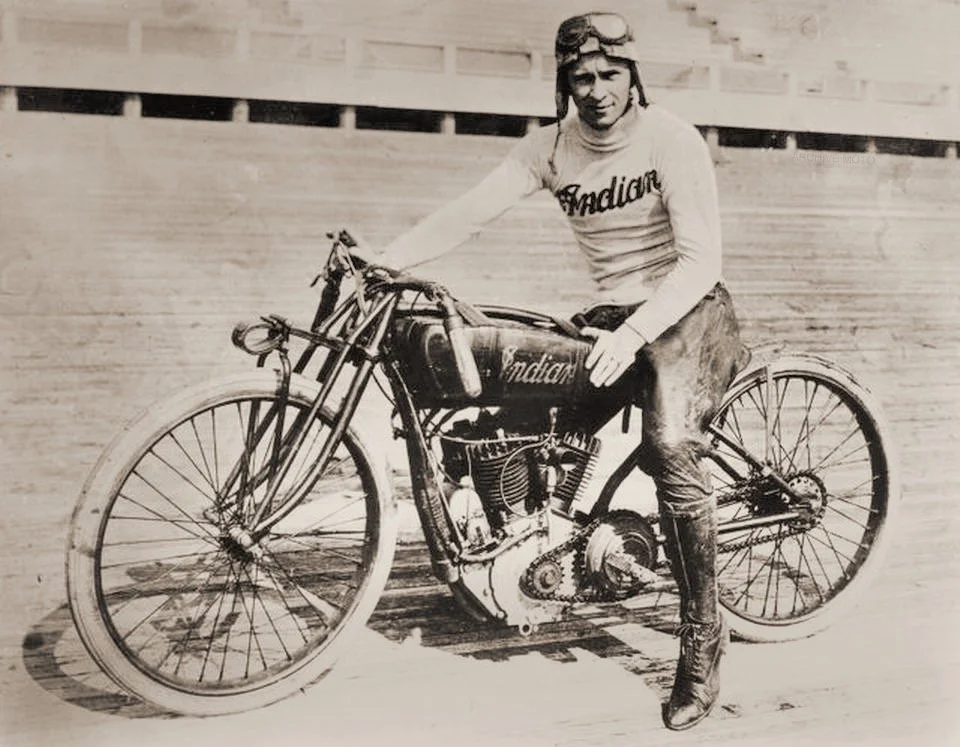

Ralph Hepburn onboard his Indian “Daytona” factory racer on the boards of the San Carlos Speedway, May 14, 1922.

Nearly 100 years ago, on May 14, 1922, a handful of the world's most notable and beloved motorcycle racers walked onto the timbers of the San Carlos Speedway to compete in a series of thrilling board track races. Despite being at the height of its first Golden Era, the momentum of Class A motorcycle racing in America was beginning to stall. Racings popularity had been a wave fueled by public enthusiasm and the limitless financial support of the big factories, but by 1922 that wave seemed to have crested. The once sensational, circular board track motordromes that had captivated the country a decade before had been ghosts for years by 1922. They had been replaced by massive, oval-shaped board track super speedways beginning in 1915, and though another 11 wooden speedways were still to come, the majority were reserved for increasingly popular automobile competition. Even still, the shelf-life of the immense wooden speedways was typically quite short, their high cost of maintenance and vulnerability to the elements making them viable for only a few years.

Annual hill climb competitions were growing in popularity, but the factories had yet to back the more localized events. Even local dealerships in the Northeast banded together to stop official sponsorship after pushback from privateer climbers who couldn't compete with the dealer-backed and highly tuned custom hillclimb machines. Though the professionals still traveled the country to the big board tracks, the most frequent motorcycle races at that time were the dirt track races. Nearly every major city had one of the tracks, either in the form of a new state fairground or an ancient relic of the horse trotting parks of the past. Still, such venues often dictated smaller displacement machines as the fire-breathing big-twins of Class A competition were a handful on a short dirt oval. The factories slowly began reintroducing production singles in response to preferences in the European marketplace, but factory racing singles wouldn't gain traction until the later part of the decade. Lastly, the age of the slight-but-mighty 45 CI, the platform which would dominate flat track racing in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, had not yet begun. By the late teens, Harley-Davidson and Indian had already agreed to begin limiting factory support for engine size on dirt tracks, going so far as to handicap their "big-twin" racers. The result was a rash of blanked-off twins, racing specials that had one cylinder removed, the port covered up with a plate to restrict displacement.

Harley-Davidson, a company that had so reluctantly held back from supporting a factory racing program during the grand age of the American Motordrome, had exploded onto the professional racing scene in 1915, producing one of the top factory programs in the world seemingly overnight. The machines, financial support, and stable of iconic riders made the Harley-Davidson racing team a dominant force in the mid-to-late teens, taking much of the momentum away from Indian who had essentially owned the sport of racing since the motorcycle was first introduced. After the brief pause in professional competition during America's involvement in WWI, the Milwaukee team reached legendary new heights; this was the infamous age of the Wrecking Crew. However, just as it seemed that the Harley-Davidson program was reaching its stride, the factory pulled support for the program at the end of 1921. The moment marked the beginning of the decline of high speed, factory Class A racing in America, the final days of the lionized professional superstar racers, and the inevitable fading of America's infamous board track speedways. Harley's departure took the sport's momentum and left many of America's most iconic racers to find a new way to compete.

The greatest motorcycle racers in the world occupied Bill Ottaway's stables in Milwaukee at that moment, so with the change in Harley-Davidson's support came a shake-up in the sport. Some racers, like team veterans Joe Wolters and Leslie "Red" Parkhurst, chose to retire from the sport altogether. Other Wrecking Crew icons like Otto Walker, Ray Weishaar, and Fred Ludlow were given the option to acquire their racing specials and compete without the company's full backing. Having just lost their star rider Shrimp Burns, who died flat-track racing a big Indian 8-valve on August 21, 1921, Indian needed new talent. The Springfield manufacturer scored two of Harley's best in the shake-up, Ralph Hepburn, who had arguably had become the best rider in the country, and the young Jim Davis, who would bounce back and forth between HD and Indian through the remainder of the 1920s.

Since the return of professional racing for Harley, Hepburn had been a force, winning the 200-Mile national Championship at Ascot in June of 1919, placing second at Marion that same year behind Parkhurst, and winning the Dodge City 300 on July 4, 1921. Hep smashed all standing track records at Dodge City that year, and over the course of 1921, he brought home 33 National Championship titles for Harley-Davidson on both dirt and timber. At the beginning of the 1922 season, Hepburn was offered a ride on Floyd Dryer's Indian sidecar set up after a spill at a race in Milwaukee. Hepburn took home a national sidecar title and was quickly signed up to race for the Wig-Wam. The folks in Springfield ensured that their new star riders had the best machine possible, outfitting Hepburn with a big-valve Powerplus racing machine, known bet as a "Daytona" for its record-smashing runs on the infamous beach at the hands of Eugene Walker in 1920. By the time the races at San Carlos kicked off on May 14, he was in top form onboard his new Indian Daytona—Hep was the man to beat among his former teammates still running their Milwaukee iron.

The massive, 1.25-mile-long wooden speedway featured steep 38-degree banking in each corner was built in San Carlos, California, about 20 miles south of San Francisco and just a bit north of Palo Alto. Jack Prince, the godfather of the American motordrome, had just completed construction of the nearby Cotati Speedway, located about 70 miles north, when he ventured to San Carlos to break ground in the Fall of 1921. Prince and his partner Art Pillsbury secured the land, about 140 acres at the intersections of Brittan Ave., Old Country Rd. and Industrial Rd. and secured upwards of half a million dollars to begin construction. The grand opening automobile races were held as the gates first parted to nearly 40,000 spectators on December 11, 1921. The heavy purse, a total of $25,000, drew a large international field of some of the best pioneer auto racers of the day. In his Duesenberg GP, Jimmy Murphy took the top honors against legends like Ralph DePalma, Eddie Miller, and Eddie Hearne, setting a new 250-mile record at 111.8 mph in the process.

On May 14, 1922, the motorcycle races were staged and promoted by the California Highway Patrolmen's Association and drew a crowd of over 6,000. Indian's Ralph Hepburn, Jim Davis, and Bob Sargesian squared off against Fred Ludlow, Otto Walker, and Ray Weishaar, each onboard their Harley-Davidson's. Right off of the line, Ray Weishaar set the bar high, winning the 10-mile with an average speed of 110 MPH, though just barely edging past Davis and Hep. Weishaar also looked to have the second event, a miss-and-out race that ran for 7.5 miles before Hep shot past him in the last stretch, beating him across the line by inches. The remainder of the day then went to Hepburn on his crimson Daytona. He took both the 25-Mile and 50-Mile events, Davis and Weishaar being the only in the field to join him on the podium as Ludlow and Walker suffered sluggish machines and blowouts on the boards. Aside from closing out 3 of the 4 events in San Carlos that day, Hepburn also took home the Barney Oldfield Diamond Medal for "Master Ridership." Two months later, in July, Hep again returned for the Dodge City race, which had been relocated to Wichita for 1922. Hepburn won the 300-Mile National Championship, repeating his victory from the year before this time for Indian, making him the only man to repeat the victory and clinch the title for each of the two largest manufacturers.

Ralph Hepburn continued to race and win on two wheels for both Indian and Harley-Davidson for a few years, even traveling to Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. On July 4, 1925, at the famed Altoona board track speedway, Hep took a hard spill while running on his old Harley-Davidson two-cam at the 100-Mile National Championship. He broke his wrist in the crash and withdrew from the event, but Hep's incident marked the beginning of a new era for both Hepburn and Harley-Davidson. Ralph Hepburn went on to run a successful career in auto racing, competing and leading the Indy 500 at least once in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. The spill at Altoona also ushered in the rise of one of America's most iconic stars, Joe Petrali, who Hep offered his machine after Petrali's Indian didn't make it to the event. It is a story that warrants its own account and is detailed in the Archive article Smokin' Joes Big Day. To read more on Ralph Hepburn, Joe Petrali, or any other greats from the golden age of American motorcycle racing, check out the Archive Icon Series or search The Archive for more.