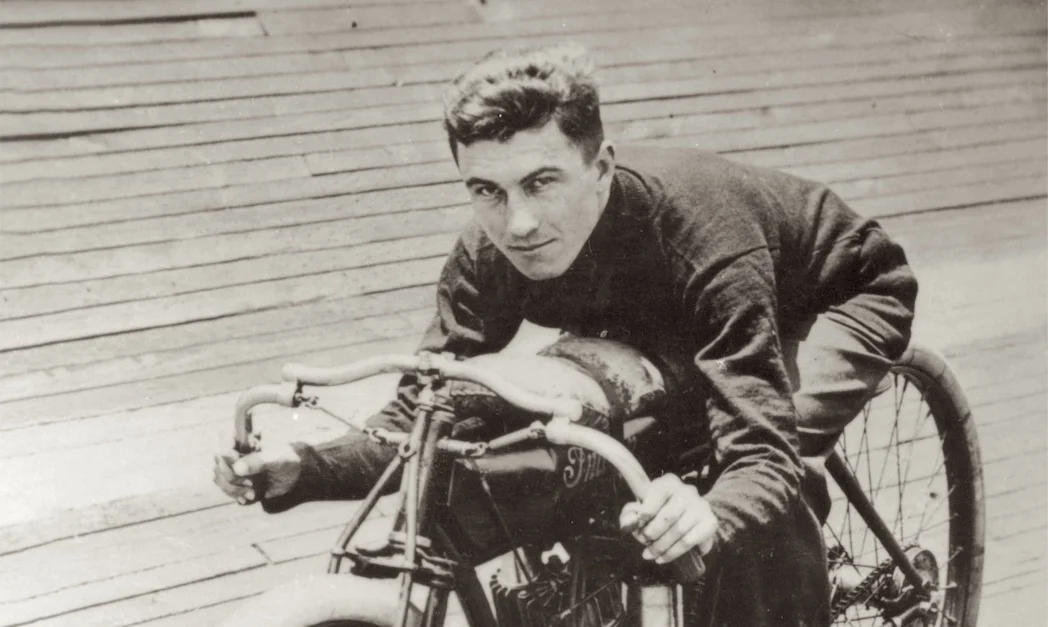

The dashing young Millionaire Morty Graves onboard his Indian factory special inside the Atlanta Motordrome, Summer 1913. Photo from The Van Order Collection

It is a rare and invaluable occasion when we get to look back through the eyes of a true American pioneer, to hear their own personal account of how a particular history occurred, and witness first hand the birth of a culture. This week at The Archive we experience a bit of what racing motorcycles in America was like in those first years at the turn of the 20th Century, just after the machines themselves were introduced. In this wonderful interview, originally published in Motorcyclist Magazine in July of 1935, Morton James Graves recalls his own glory days, racing motorcycles as a teenager and helping create a new sport as one of the first professionals in America. At the time the interview was made, Graves, also known as “Millionaire Morty” was 44 years old, an Indian dealer in Hollywood, veteran of the culture, and a founding father of the sport.

Originally from Chicago, Morty moved to Pasadena with his family when he was still a boy and by the time he was 16 years old he had begun racing motorcycles, that was in 1906. As you will read in his testimony, his interest in motorcycles began nearly as soon as the new machines were introduced, before there was any real career path as a motorcycle racer. It was the persistence, natural skill, and audacity of Graves and his contemporaries which help give birth to the sport itself, and through his career Graves would be among the heroes of the dirt and timber, one of the fastest men on Earth. Graves raced for Excelsior, Merkel, and Indian, as well as a few European oddballs in the early days like Peugeot, Minerva, and NSU. He was among the first class of riders to turn professional, acquire sponsorship deals, and set speed records on dirt tracks and board track motordromes.

By 1915 the spills and mechanical failures had taken their toll on Graves and at 25 years old he threw in the towel, though he did still list “Motorcycle Racer” as his occupation on his WWI Selective Service Draft Card. Like so many professional riders of the era though, Graves voluntarily enlisted in the US Army in 1917, he saw no service overseas before the Armistice and was discharged honorably a Private. After the war he married, had children, and opened up an Indian dealership at 5960 Sunset Boulevard in Los Angles where he worked until his death on New Years Eve, 1944. Though the dates and events jump around a bit during Morty’s interview, this rare glimpse into those earliest of days are a fascinating and informative trip back to the birth of speed.

“Mine was not an office boy to president sort of racing career. Contrary to the experience of many racing men, I had not spent a lot of time on a motorcycle prior to the time I started racing. I rode first at the age of sixteen in 1906 and I started right out to race. Of course my early races were not victorious ones. But as I learned to ride and to control a machine I also learned to race. In those early days, before a mile-a-minute had become an actuality we used wood rims with bicycle spokes. They were really sulky rims. We also used open ports which would uncover about one half inch from the bottom of the stroke. The ports helped the escapement of gas and also helped to keep your legs warm. The valves in those machines were not so large as in later designs and the ports were considered quite a help.

My first equipment was strictly stock. Then I got into the semi-stock class and finally acquired my first real factory racing job, a Hedstrom motor built at the Indian factory, in 1907. While I had been working up to this motor a fellow by the name of Collins, in November, 1906, turned a mile-a-minute at the old Agricultural Park, in Los Angeles. He had ridden a Peugeot, a French 5-horse twin. So with the new machine I really went out to win and my first attempt was at 65 m.p.h. in a race on old Ascot. My competition that day included men from the ranks of the popular racers such as: Eddie Hasha, Lee Humiston, Al Ward, Johnny Albright, Ray Seymour, Al Earhart, Charley Balke, William Samuelson, Paul Derkum, Walter Collins, Dave Kinney, Billy Hoag, Gal Blaeylock, Jack Fletcher, Arthur Mitchel, Fred Whittier, Irwin Knappe, Jake De Rosier, J. Howard Schaeffer, Bert “Spot” Bruggerman, Percy Powers, and Roy Artley. My 65 mile average brought me a victory.

With that as encouragement I was to ride in many events during the next few years, mostly dirt track races, some road races and a few enduros. As event followed event I was also to run into some funny experiences. One incident which always stuck in my mind happened during a one-hour race at Santa Ana, California. We started the race with between twenty and twenty-five riders. The tracks were always very dusty. With that big a field it was only a moment until we were all riding blind. Then Spot Bruggerman fell on the north turn. Everyone in the whole field missed him in spite of all that dust. I ran over his machine and was spilled. Spot jumped up and ran to a track guard who was mounted on a horse, he dragged the guard off. Jumping on the horse he started to ride on around the track toward the pits. He urged the horse to its utmost, while whizzing by on all sides were the fast going motors. It was an odd sight. Arriving at the pits Spot discarded the horse and grabbed a new motor on which he started out. However, he was disqualified by the F.A.M. officials. It was later found he had broken a bone in his foot.

At that time nearly every spill meant being in the hospital or being laid up for a while. At [Playa] Del Rey we all rode in stocking caps and wore tights. It was a showmanship angle and appealed to the crowds. The boards were all unsurfaced lumber and when a fellow fell in one of those outfits he really took on some splinters to say nothing of burns. The board tracks had about a 50 degree bank on the turns and as much as 32 degrees on the straightaways. We worked up to the break neck speed of a mile in 48.2 [seconds] which was some going for that equipment. (Approximately 75 m.p.h.)

About that time I came up with a German machine, N.S.U., which was a 61 inch job. It had a belt drive, the belt being 3 ½ inches wide. The pulley was about 5 ½ inches wide. The motor was very fast but it was hung high in the frame and therefore the outfit had a very high center of gravity. At first I was discouraged. Then I found I could lay the machine over toward the pole and the pulley would not only hit the track but would hold. That meant I could take a turn wide open without a bit of slide. A pulley would wear out in about three meets but I won a lot of races that way.

Finally, Freddie Huyck showed up on the West Coast from Chicago to break some records. He saw my tactics with the pulley and worked up some match races. He had a machine with a much lower center of gravity. We were to have French starts. That meant the pole man could set the pace and if the outside man could be made to cross the starting line ahead of him the event was considered lost right there. He knew I had to take the corners fast with the N.S.U. so, he rode as slow as he could coming out of the last turn and on the way up to the line for the start. We were to have 5 heats in the match. The first day I couldn’t go around as slow as he did and three times I was made to cross the line ahead of him.

We were to continue the match the following Sunday. The first heat he drew the pole and I fell off trying to keep from crossing the start ahead of him. I lost that heat. Then I drew the pole and set a fast start, after which I rode on the pulley and beat him. The next heat I drew the pole again and repeated. Then he drew the pole and of course set a slow pace. For once I managed to stay behind and we got the gun after which I gave that pulley the ride of its life and thus managed to win three heats. Things like that were considered fair in those days but often the wins or losses were on the basis of things outside the actual riding or racing. A new track was built in 1908 which was so fast that all the existing records were broken. It fell my lot to break everything from the two-miles at 1 [minute] 17 [seconds] to the twenty-five miles at 16 [minutes] 36 4/5 [seconds]. I set a new high of 45 1/5 seconds for the mile. (Approximately 80 m.p.h.) We were shooting then for the 90 m.p.h. mark.

The first factory teams began to appear in 1909. At the Point Breeze track near Philadelphia, at a national championship event, we had Indian, Merkle, Thor, N.S.U., Peugeot, Minerva, Anzani, and Clement teams. The last five were foreign. We found that teams could work pretty well together so the practice was improved and continued. We rode on that basis for the next couple years. We were constantly getting more speed, more experimental equipment and more experiences. At Huston, in 1913, an odd incident happened. Tex Richard had his front wheel clipped by Spot Bruggerman right near the finish. Tex. who was going wide open, turned toward the grand stand. He cleared the crash wall and about 14 rows of seats and then disappeared from sight over the top. The ground outside had just been plowed and there was Tex so far buried that it was difficult to pick him out. He left an imprint of his whole body in the ground to the depth of several inches. It turned out that not a bone was broken and he was walking around the next afternoon.

On the Maywood Speedway in Chicago, a Henderson racing job showed up for some tests. We had had no experience with fours. The first man out went into the turn with the motor well over. When he went to pick it up he found he couldn’t. So he went through the infield fence. The machine was rebuilt and brought back out. I was selected to give it a trial. Not knowing much about the first man’s problem I went into the turn fast and when I came to pick it up for the straightaway I found it was just the same as nailed down. So I too crashed the infield fence. Several attempts were made with different riders. And everyone went through the fence at the same spot. We just couldn’t overcome the torque.

A rather humorous happening was at the Point Breeze track. Arthur Chappel, who was on the Merkle team with Cannonball Baker, showed up for a race. The track there was triangle shaped. It was tricky and most new riders tried it out before racing. I guess Chappel, who was a very good dirt track man, felt kind of a big shot that day. He passed up the try-out, having someone else run his motor around for him. When it came time for the race he even showed up in a dressing gown. It was all very impressive with the crowd. He got on his machine. Then he came down past the stand for the flag. An arm of the bay came in past the first turn. Chappel missed the turn and went into the bay. He got tangled up in the weeds and almost drowned. That was the end of the boy for that day. In that same meet my brake, which was the old style coaster brake, locked throwing me in front of the field. They ran over everything but me.

I was not so lucky at Oklahoma City. We were in the final stages of a road race. I was in third place with a chance of getting second. If I could gain a little on one turn I thought I’d make it. So I decided to use the curb as a bank. A slight bump made me miss the curb entirely. I went into the front of a store and stopped with the muffler pipe on my chest. This was my worst accident, the hot pipe giving me a burn which kept me in for sometime.

In September, 1915, I retired from racing. I had a seven mile lead and then at the end of 299 miles in a 300-mile event [Dodge City 300] the bottom dropped out of my gas tank. I had been thinking of retiring for some months and this disgusted me to the point that I actually quit. I enjoyed racing and it was primarily for that reason that I rode. I made and lost a lot of money while riding. Although I still ride motorcycles I am past racing age. I made many friends during that period and it is a real pleasure to meet again those old timers, or to read about them in the annals of motorcycling. Many of the old records have since been broken as new riders and new equipment came along. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the opportunity of breaking records and setting new world marks, and I still think some of those marks were good ones considering the track conditions and equipment we had.”~Morton James Graves, “Millionaire Morty”