Like most of America's earliest professional motorcycle racers, Cleo Francis Pineau was far from average. A native of Albuquerque, NM., it is said that his restless nature led him to drop out of school in the 6th grade, shortly after which he began racing motorcycles. He was a staple member of the Flying Merkel factory racing team, in the company of such greats as Lee Taylor, Ralph DePalma, Charlie Balke, and Maldwyn Jones. On board his trusty Merkel, Pineau crisscrossed the country in the early teens racing at the most prestigious events of the day, including the 300 mile endurance competition held in Savannah in 1913 and 1914.

With the suspension of professional racing during WWI many racers enlisted for service. Not satisfied with just any role in the war Pineau enlisted in the RAF and became a fighter pilot. He earned his title of Ace after his sixth confirmed kill during aerial dogfighting in France. He himself was then shot down in October of 1918 and held captive in a German prisoner camp. Upon his safe release Pineau was decorated with countless medals and the highest honors from England, France, and Belgium, and even received a hand written letter from King George V welcoming his safe return.

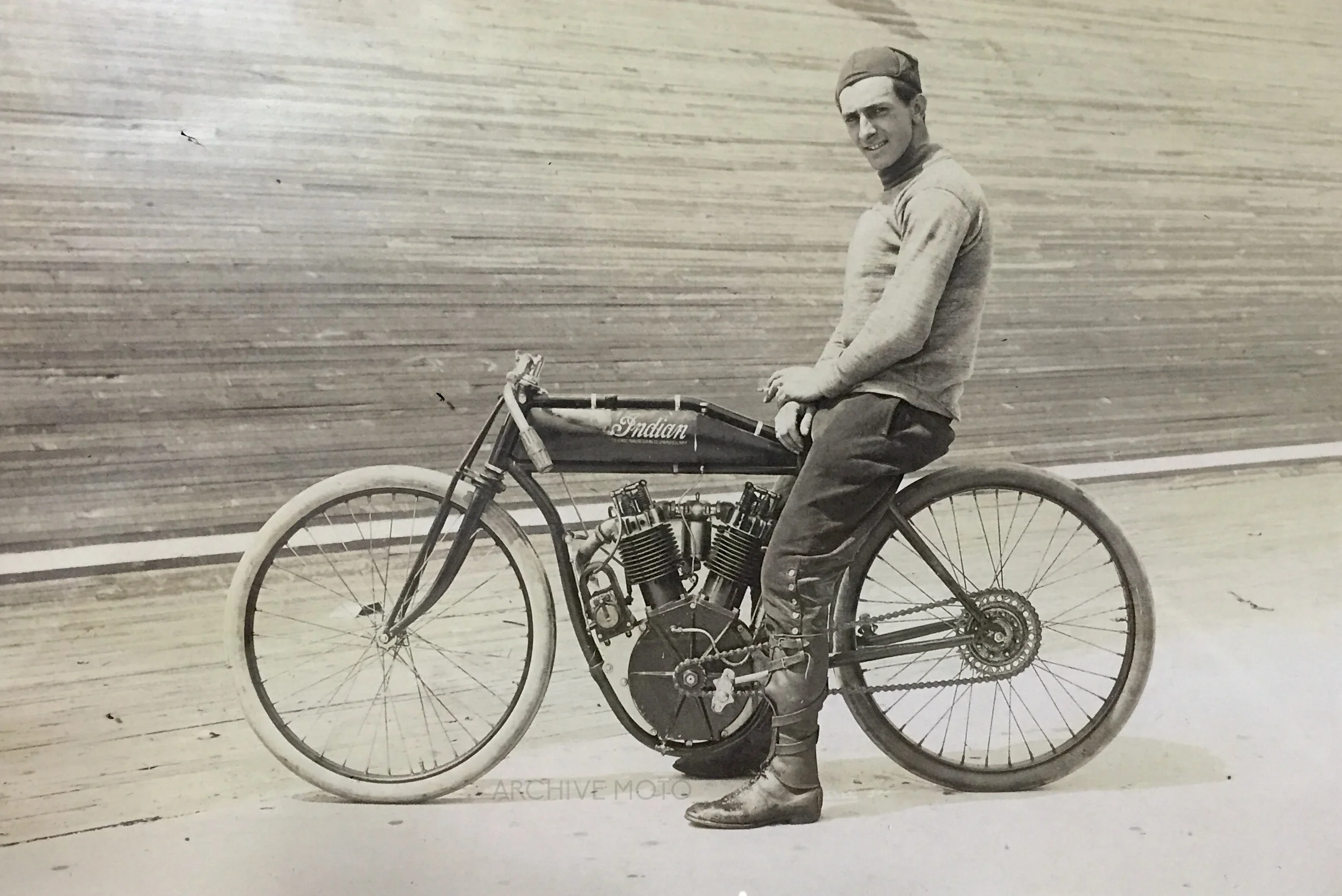

After the war Pineau continued his motorcycle racing career, but by the late 1920's he had ventured into the business world by forming the Radiant Steel Products Company which is still in operation to this day. In addition to his steel company, Pineau also established the Williamsport-Lycoming Airport and was accompanied by his friends and American aviation icons Wiley Post and Amelia Earhart during the opening dedication ceremony. In this photo 20 year old C.F. Pineau sits steely-eyed atop his Merkel single during the June 1914 races held in Toledo. Pineau's Flying Merkel teammate Lee Taylor took the checkered flag that day, and a few months later beat him and the rest of the field again at the 1914 Savannah 300, though his victory in Georgia was on board an Indian twin.

By 1919 the world had finally come out of the desolate haze created by the first World War and in America, motorcycle racing experienced an energized rebirth. Though the once countless manufacturers of American motorcycles had atrophied to a small handful, those who had faired well on the track before the war were now the dominant brands. Indian and Excelsior were early powerhouses in the arena of racing, but they were now joined by a sturdy and hungry Harley-Davidson. The machines became engineered for speed, Big Valve Excelsiors, Keystone framed Harleys and Indians, and new power plants like Indian's Powerplus and Harley's 8-valves made the spectacle of racing even more intoxicating. The exhilarating circular motordrome board tracks had almost all been abandoned before the war and races now took place on dirt road courses, or the handful of large board track speedways. The FAM (Federation of American Motorcyclists) who had helped give birth to organized motorcycle racing in this country had diminished and was replaced by a new sanctioning body, the M&ATA (Motorcycle & Allied Trade Association) who would eventually turn into the modern AMA (American Motorcycle Association). A lot of early board track stars who had transitioned from cycle racing had sadly either died or retired, but a new breed of professional had been mentored and took to the sport just as vigorously. Factory teams busted at the seams with talent and they all came out for the September race in Marion. Otto Walker, Joe Wolters, Shrimp Burns, Bob Perry, Leslie Parkhurst, Teddy Carroll, Ray Weishaar, and Maldwyn Jones were just a few of the now legendary men who took to the 5.17 mile Indiana road course that day. Leslie "Red" Parkhurst, a longtime key player on the Harley team took the checkered flag in Marion, followed by his teammates Ralph Hepburn and Otto Walker to close out the podium for the Milwaukee factory. While you watch notice how big everyone's smile seems to be, this was our revival.

Within a single decade of their American introduction, motorcycles had matured at a frenzied pace, quickly evolving from brittle, finicky gadgets to bruiting, highly-specialized machines. A new American industry exploded, public enthusiasm was brimming over, and the world applauded at the rise of an invigorating new sport. By 1909 the board track motordrome, one of the most romanticized facets ofmotorcycle racing culture was born. A natural derivative of the intensely popular Velodrome bicycle racing, the premier sport of the late 19th century, the American motordrome stadium offered attendees a new level of exhilaration, anticipation, and thrilling danger. In the spring of 1909 the Los Angeles Coliseum, America's first motorcycle board track was alive with the menacing pop of open exhaust, and by 1912 nearly a dozen similar tracks had been erected across the the country.

This photo comes from that The Golden Age of motorcycle racing, a time when motorcycles filled the city streets and county roads of America, and a time when families poured into the infields and grandstands of their closest board track motordromes. This was the era that racing itself was defined, a time in which men established for future icons what it took to be fast and what it meant to be a racer. Taken in July of 1912 inside the newly constructed motordrome in Columbus, Ohio this photo captures Indian factory team rider and Detroit native Don Klark onboard a Big-Base Indian 8-Valve. The earliest version of Indian’s 61ci 8-Valve machines, this model with its rigid-frame, large cases, small tank, and direct-drive chain embodies the simplistic elegance and raw power that can only be seen in board track motorcycles from the era. Just as this Big-Base 8-Valve epitomizes the machines of the American board tracks so too does Klark personify what it meant to be a racer in those early days. The dare-devil grin, cigarette in hand, and wearing what could be considered an uniform best suited for an early autumn stroll Klark, like the other racing pioneers was a gentleman of true grit.

Possibly one of the rarest American motorcycles ever assembled, the Cyclone powered, OHC Reading Standard factory works racer photographed with legend Ray Creviston on the company dock in 1921. Beginning in 1903, Reading Standard began manufacturing high quality American motorcycles known for their durability, and from the start the Pennsylvania based company garnered accolades for their performance on the track.

By the teens many of the numerous American motorcycle manufacturers had begun to fade away leaving those with stakes in the racing game like Reading Standard, Indian, Excelsior, Flying Merkel, and a rising Harley-Davidson to grow even stronger. Commonly known as the "big three," Harley-Davidson, Indian, and Excelsior turned their dominance on the track into expansive distribution networks and iconic marketing campaigns. As a result Reading Standard, without the ever deepening pockets of their rivals gradually lost their competitive edge despite seeing their best sales years in the late teens. Riding a wave of enthusiasm as a result of the highest production numbers in the companies history, RS attempted to revitalize their company by developing a pure racer in 1921. The American motorcycle scene had become intensely competitive after WWI, and RS had to raise the stakes if they were going to compete with the race-proven thoroughbreds of Harley-Davidson and Indian. Unlike any other machine being produced by the company at the time, this unique cam driven overhead valve engine was actually salvaged from the parts bins of the once mighty Cyclone company, who closed their doors in 1916.

Creviston shipped out to Los Angeles in January of 1921 with the hopes of riding the new motorcycle to victory, a move the company hoped to reestablish the brand as a major player in the United States. A great deal of interest and speculation surrounded the new RS, everyone was curious as to the speed and performance given the combination of the esteemed reputation of RS with the high end performance of the Cyclone power plant. However, Creviston, who along with Dave Kinnie were instrumental in the development of the machine kept information about the its capabilities rather quiet, wanting to let the anticipation build until people, and journalists could witness it for themselves. His first stop on the west coast tour was set for the mile long Fresno Speedway board track, where early reports clocked him at over 100 mph. The machine’s debut at Fresno unfortunately began the sequence of heartbreak for Creviston and Reading Standard as the new hopeful heavyweight fell short due to technical issues with the motor. And as if to add insult to injury, Otto Walker, Captain of the legendary Harley-Davidson Wrecking Crew decimated the competition that day becoming the first man to officially claim a race victory at an average speed of over 100 mph on board a “banjo” 2-cam, 8-valve HD.

Unfortunately the machine could not shake the bad luck it experienced at its debut at the Fresno Speedway, and the subsequent races that Creviston entered most often resulted in mechanical failure. The wave of hype that preceded Creviston and his wonderful Reading Standard “Eight” crested and broke as the machine consistently limped into the pits with the same mechanical issues that plagued Cyclone engineers in the teens. Despite a grand effort and by Creviston and the RS crew, the 1921 season came to a close without a single win. Sadly, the effort that was meant to bolster a struggling company in-turn drained the limited coffers of the Pennsylvania based Reading Standard and by 1922 the company was preparing to close its doors. Creviston went on to pen a contract with Indian, and in February of 1923 it was announced that the Cleveland Motorcycle Manufacturing Company had acquired Reading Standard, putting an end to the fourth longest running American motorcycle manufacturer, the prestigious Reading Standard.

www.ArchiveMoto.com