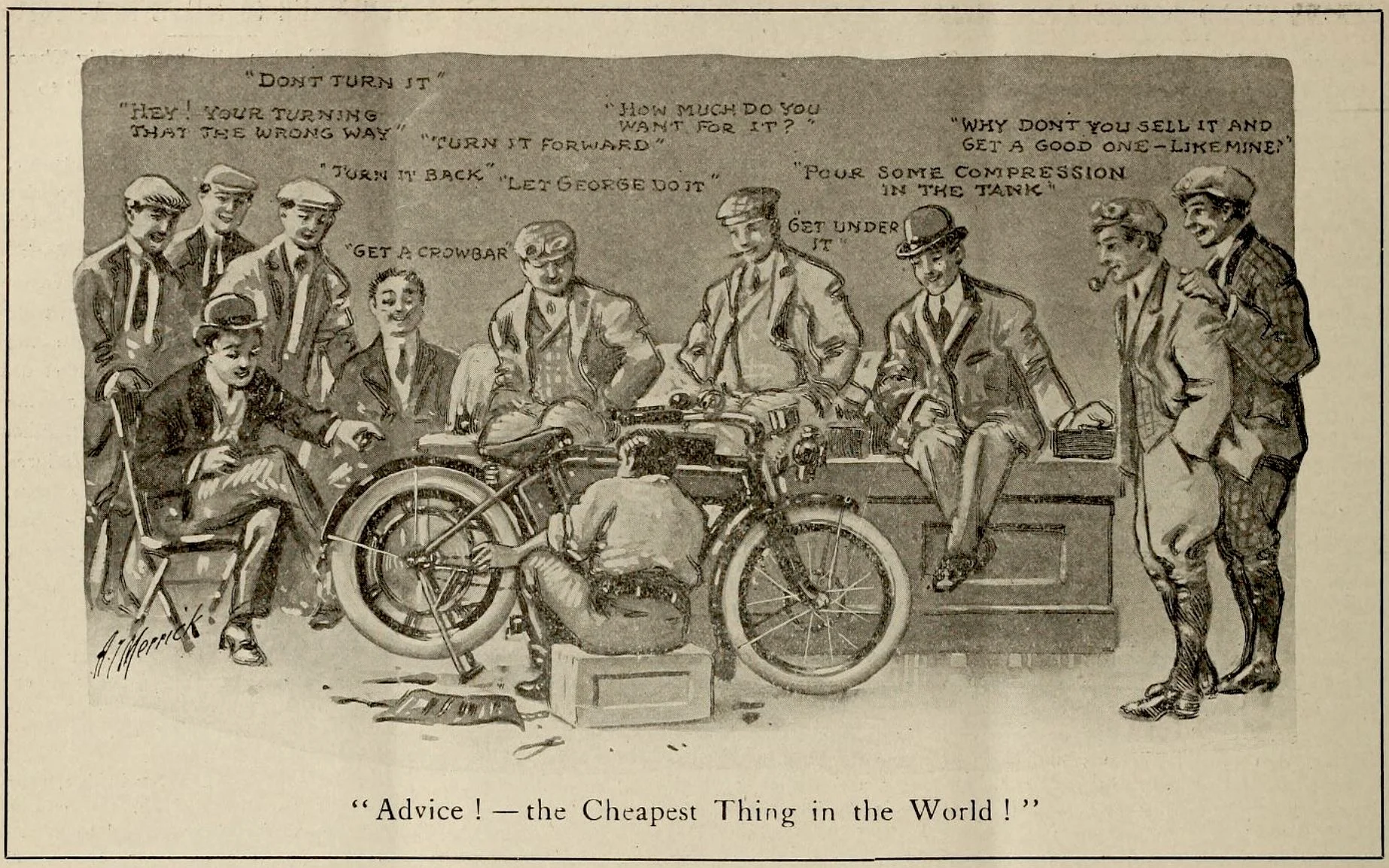

The more things change, the more they stay the same. November 1910.

Today's post is in honor of the MotoGP race being held on the hallowed ground of Indianapolis this Sunday.

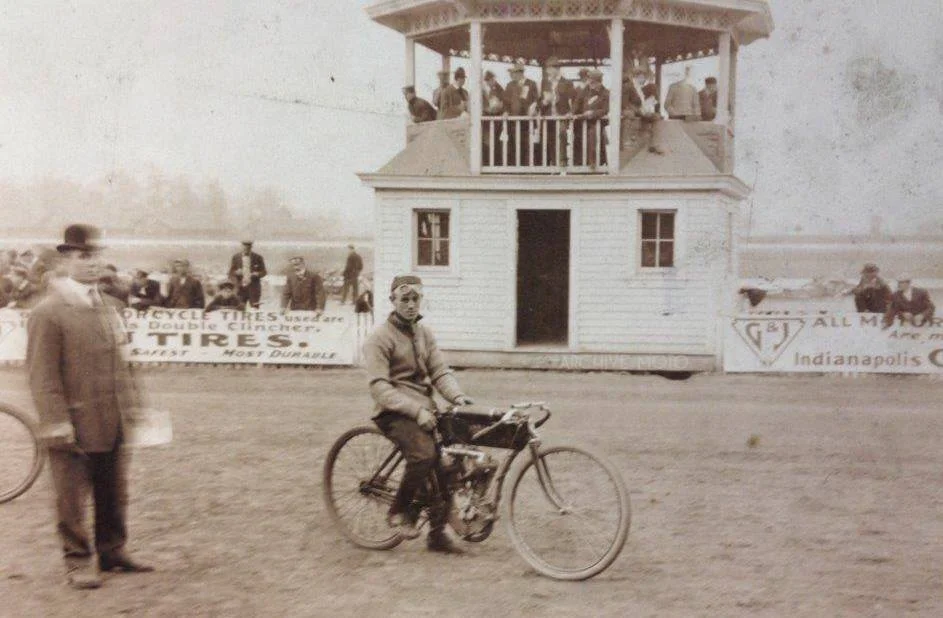

This photo captures a moment from the earliest days of American motorcycle racing. Before the massive super speedways and infamous board track motordromes, before the fervent manufacturer arms races and mighty advertising economy, and before sponsorship and stardom daring young men obsessed with speed and victory barreled around local horse tracks in tremendous clouds of oily dust. Motorcycles were less than a decade old, really no more than stout bicycles with gasoline engines strapped on, but already they had become the main attraction at fairgrounds across the country.

On October 10th, 1908 the Indiana Motorcycle Club held their first event on the 1-mile dirt horse track at the State Fairgrounds in Indianapolis. A large number of daring early motorcyclist arrived to test their mettle, but it was a young Chicago native named Freddie Huyck that would take the day. One of America's pioneer motorcycle racers, Huyck won every race he entered that day and set a new 1-mile record in a shade over 56 seconds. Huyck dominated the large field of competitors on board a very special loop-frame prototype Indian twin, one of only three newly developed that year by Oscar Hedstrom, the innovative engineer at the Hendee Manufacturing Company.

The new design would mark the beginning of a transition, the dawn of the modern motorcycle. Local organizations like the Indiana Motorcycle Club would continue to grow, all the while organizing and promoting motorcycle races. In a few short months the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, America's legendary racing mecca would be constructed a few blocks from the fairgrounds. Within a year Indian signed its first factory racing star Jake DeRosier, soon followed by Hyuck, and America's first board track motordrome was opened in Los Angeles. A new era had begun to take shape, motorcycle racings crowded hour, a time in which competition, innovation, and fearlessness gave rise to a new industry and established one of America's richest cultural strands. Here, mounted on his rare Indian and donning his signature haunting blank stare is Chicago's young star Freddie Huyck on that victorious day in Indianapolis, Oct. 10th, 1908.

One of the first and most popular forms of early American motorcycle racing was the long distance endurance competition. While local horse tracks provided the perfect venue for pioneering racers and enthusiasts alike, the endurance contest gave riders a chance to test themselves and their machines to the breaking point, covering hundreds of miles over multiple days in the pursuit of a perfect score. For those that finished, a perfect score was typically 1,000 points with deductions for early and late times at checkpoints along the route. The first of these competitions was started by the Metropole Cycle Club of New York in 1902. The seminal 2 day event between new York and Boston saw 31 eager gentlemen enter and only 13 remain by the final tally, establishing the idea that in these type competitions it wasn’t about winning as much as it was about surviving.

With the formation of the Federation of American Motorcyclists in 1903 so too came the official sanctioning and scoring of a national endurance and reliability run, each year swelling with participants and national publicity. Only 16 of the 31 entrants survived the 1903 run, only 12 of 27 in 1904, and a record breaking 34 of the 44 starters survived in 1905... though it must be noted that the ’05 contest was only 250 miles over a single day. The numbers of entrants continued to grow over the next few years, and the number of survivors typically stood around 1/3 to half of the starter pool.

A record 126 men registered their machines for the 9th annual FAM Endurance Contest in 1910. The race began at 7am in front of the Century Motor Club HQ located at 1606 N. Broad St in Philadelphia, PA. The 505.7 mile route was planned over 3, roughly 165-mile days through Reading, Hackettstown, Newburg, Newark, Absecon, and back to the starting line in Philly. Of the 126 entrants, 125 actually started and included men from all aspects of motorcycling culture. Professional racers, amateur hopefuls, daily commuters, manufacturer-backed teams, and local clubmen all set out, two at a time. The convoy was dominated by the big racing brands of the day, Indian, Merkel, Excelsior, Thor, and Reading Standard, but a number of smaller American makes made it into the bunch including MM, Minneapolis, Yale, Bradley, Emblem, Reliance, Mack, New Era, Haverford, Marvel, C.V.S., and Pierce.

The first day covered 170.6 miles to Stroudsburg and was predicted to be the most challenging leg given the hilly terrain and poor road condition, and as it happened would be the end of nearly 90 of the competitors within just over an hour. A torrential downpour struck the riders on the thick clay roads outside of Hackettstown near the aptly named Hope, PA. With so many riders losing hundreds of points and failing to complete the course at this point it became referred to as the “Battlefield” of Hope, only 27 riders remained after the first day.

Of those few left standing in the 1910 contest were these two fine gentlemen and their 4HP belt-driven singles customized with their names on the tanks. Wearing the #8 is William S. Harley, founding member of the Motor Co. and in the #7 is arguably Harley-Davidson’s earliest racer Walter Davidson. It was Walter, brother of founding member Arthur Davidson that joined the company in 1907 and promptly won the diamond award and a perfect score of 1,000 points in the 1908 FAM Endurance Contest. Both Harley and Davidson stand in front of the C.R. Zacharias Garage in Asbury Park, NJ on the final day of the contest. They made it through the Battlefield of Hope but not unscathed, William S. Harley lost 13 points for tardiness at the checkpoint, Davidson lost 84. In the end the Harley-Davidson brass were among the 24 survivors of the 1910 FAM Endurance Contest, but the skirmish in the Pennsylvania clay prevented them from perfect scores. Three boys from Thor took the only perfect scores in 1910, Harley finished with a near perfect score of 986, Davidson 916, but Harley-Davidson counted it as a victory and I’m sure converted the outing into at least a few sales.

It was on this day, July 30th in 1913 that yet another tragic accident occurred on the boards of an American motordrome, claiming the lives of eight, including that of racing pioneer Odin Johnson. Called the "Salt Lake Marvel," Johnson left his career as a lineman for a telephone company in Salt Lake City to began racing motorcycles in the spring of 1911. Right away Johnson became no stranger to incidents on the boards, within his first year of racing Johnson was involved in several fatal accidents on his local track, the Wandamere Motordrome.

At the end of a race in June of 1912, Johnson was drifting back towards the bottom of the track after having cut the power to his machine when he was struck by Heinie Potter, a local police officer and amateur racer, Potter did not survive. The very next month Johnson was again in a mixup which took the life of fellow local racing star Harry Davis. According to reports, Davis clipped Johnson’s machine while attempting to pass, sending him flying out of control and into the stands. A local girl, Grace Cunningham was struck and later died as a result of her injuries, her friend Elizabeth Jensen nearly escaped death and was listed as one of the four spectators seriously injured. Interestingly, Jensen and Johnson became friends after the tragedy and were married later that year.

In July, Johnson and his brother Ben, also a racer, were in the stands watching local rider Mat Warden run a race on Johnson’s bike. The machine was owned by the track but had been Johnson’s for the 1912 season. When Warden started up the steep banking at the Salt Lake track, the rear axel snapped, sending Warden quickly veering back towards the bottom. Luckily no one was injured as a result, however after inspection mechanic J.A. McNeil determined that someone had taken a saw to the axel in an attempt to sabotage the event. Both McNeil and Johnson were initially investigated but were cleared when a man later confessed to cutting the axel.

For the 1913 season Johnson ventured to the Luna Park Motordrome in Cleveland, where he set up camp and began running races in the area. By June he had become the captain of the Cincinnati road team and was being pitted against Chicago’s captain Joe Wolters at the Riverview Stadium outside of Chicago. It was for the American League championship races, which included Cincinnati, Cleveland, Chicago, and Detroit, an St. Louis that Johnson ventured to the newly constructed Lagoon Motordrome in Ludlow, Kentucky.

With continuous banked turns of 60 degrees, the 1/4 mile circular drome at Ludlow was one of the steepest in the country and was heralded as the safest. The track opened on June 22nd under the lights to a crowd of over 4,000 people. It was one month later when, on the evening of July 30th Odin Johnson, running towards the top of the track lost control of his machine and veered towards the crowd. Johnson struck a light post, snapping it in half andsmashing in his skull. The wiring from the light post then ignited the fuel from Johnson’s wrecked Indian, burning “no fewer than 35 people” according to the local press. A total of Eight people, including Johnson died that evening; two women, two men, and three children the youngest of which was a 5 year old boy. The 24 year old Johnson had just sent a telegraph home before the race that evening, telling his family of his successes, his new road machine, and his and Elizabeth’s excitement over payments they were making on their first home.

The tragedy at Lagoon came only months after the infamous accident at the Valisburg Motordrome, which also took the lives of 8 people, including racers Eddie Hasha and Johnny Albright. With the rising death toll public opinion was beginning to turn against the dangerous and thrilling motordromes. The motordrome boom was at its height in 1913, less than 10 more circular wooden tracks would be constructed and those that were already operational would not see their gates opened for much longer. The Lagoon track was able to reopen after the tragic event of July 30th, but like the rest of America’s short lived circular motordromes it would not see the other side of WWI.

This photo is from Johnson's home track, the Wandamere Motordrome in Salt Lake City, Utah taken on May 31st 1912. It was the first day of the 1912 season, only days before the death of H.F. Johnson. I believe Odin Johnson is second from left in the button down sweater.