Assembling the stories of early American motorcycle culture typically requires a good bit of unraveling, connecting scattered dots, and examining the smallest details of photographs. Luckily, in a time before TV and radio, the printed word conveyed the stories of the day in an endlessly entertaining fashion. Today’s post is in tribute to those verbose scribes from dawn of our culture, without whom we would know little of our beginnings and historians would be tremendously uninspired.

It is taken from a small article in the November 1910 issue of Bicycling World & Motorcycle Review that offered an account of Jake DeRosier's record breaking runs at the Playa del Rey Motordrome.

“Undaunted by the refusal of the competition committee, for technical reasons, to place the seal of approval on the recent crop of records which he harvested, Jake DeRosier and his band of warriors went after Father Time’s scalp again at the Playa del Rey Motordrome, Los Angeles, Cal., on Saturday, 29th ult.,and got several strips of it.

DeRosier, who of course rode an Indian, a "7,” went after the 100 miles record and captured it in the greatest exhibition of space annihilating which that peerless speed artist ever has given. He pounded out the century in the phenomenal time of 1:15:24 2/5, which is nearly 11 minutes better than his old mark made on the same track last May.

Still more wonderful was the new hour record which DeRosier set up, when he traveled the astonishing distance of nearly 80 miles, to be exact, 79 7/8 miles, in 60 minutes, almost 1 1/3 miles a minute. This record also totally eclipses Jake’s old hour figure of 74 miles 667 yards, which he hung up last May.

Nor were the lusty speed merchants content to let Father Time get away with this punishment, for they took some more tuft at the mile distance. DeRosier also took the honors in this class, with a dash around the wooden bowl in 0:41 1/5. Ray Seymour was a close second with 0:41 2/5, and Charles Balke, was clocked in 0:41 3/5. The old record was 0:43 1/5, made by DeRosier.

The trails were duly sanctioned, and it said unofficially that the machines on being measured were found to be under the .61 cubic inches limit. Upon receipt of the official credentials from the officials, the chairman of the competition committee will determine whether or not the records will stand.”

And I thought that I used a lot of commas.

The photograph was found randomly placed in a later issue of the magazine, but shows racers and officials breaking down DeRosier’s machine for inspection after that record run at Playa. To the far right in the checkered cap is fellow racer Morty Graves, and seated in the center, black long sleeve and cap is Charlie Balke.

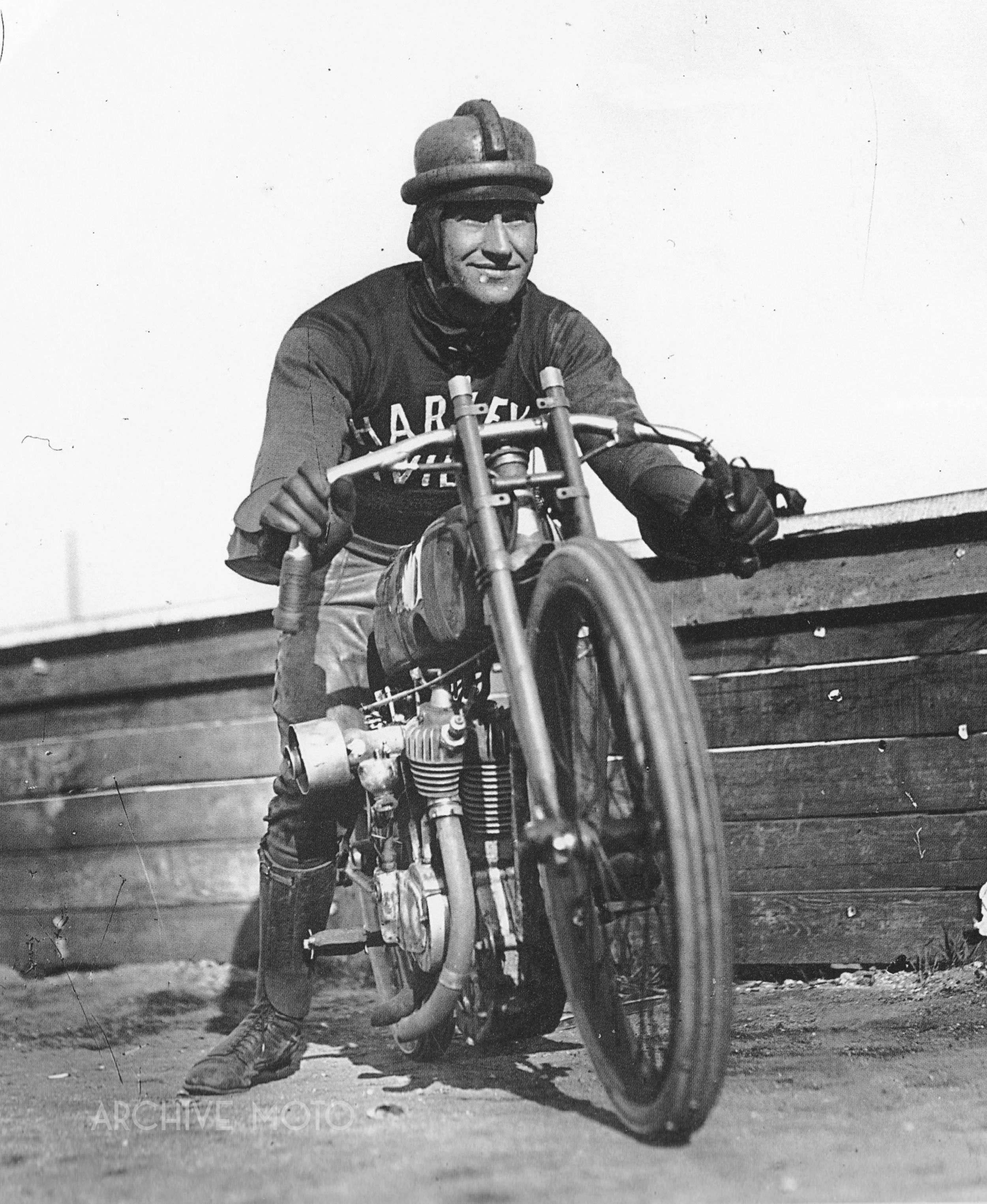

The supremely spruce Ray Tursky, Harley-Davidson dealer from Fond du Lac, Wisconsin and accomplished Class-A racer in the 1930’s. At the 1934 Jack Pine Endurance Race, a gruelling 3 day, 500-mile hard-fought battle in the wilderness of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Tursky bested a field of 87 entrants and came in first out of only 9 finishers. Tursky claimed victory in ‘34 on a top of the line 74ci VLD Flathead, Harley’s latest side-valve big twin. In 1935, equipped with yet another VLD Tursky returned to defend his title, but finished 3rd behind Jack Pine legend Oscar Lenz.

Ray Tursky, Sept. 1935.

With the suspension of professional racing in the months leading up to the United States involvement in WWI, many of America’s most notable motorcycle racers put away their goggles and jerseys in order to suit up in the olive drab wool and canvas uniform of the US Army. Dispatch and Signal Corp were some of the more common assignments for America’s motorcycling heroes, but a handful, no doubt with a hankering for the more exhilarating roles in the war enlisted for service in the aviation sector.

Most notably Cleo Pineau, one of the darlings of the Flying Merkel squad became a pilot, earning the distinction of “Ace,” and even survived being shot down and becoming a P.O.W. under the command of Kaiser Wilhelm’s son the Crown Prince. One of the brightest stars and fastest racers just before the war, Harley-Davidson’s pride, Otto Walker signed up for duty in the US Army’s aviation section. After missing the majority of the 1916 season due to a leg injury, Otto had moved from California and was living in Manhattan, working as the foreman of the Harley-Davidson Sales Co. at 226 W. 108th St. On July 20th of 1917 Otto entered his last event before service and set a new 24 hr record at the Sheepshead Bay Speedway in an HD sidecar setup, covering a distance of 1,159.75 miles.

After enlisting, Otto was trained as an electrical engineer in the US Army’s aviation division, and by May of 1918 he had arrived in France. Little information is available regarding the specific of Walker’s tour of duty, though the United States role in air combat during WWI was limited and quite outmatched until late 1918. By all accounts the former Harley-Davidson superstar was deployed in Europe for the next year, returning in the summer of 1919, but the story left untold is that Walker’s wartime souvenir, a cork and leather German pilot’s crash helmet that he acquired during his service and proudly began wearing upon his return to America.

Walker was quickly welcomed back by Bill Ottaway with a spot on Harley-Davidson's star-studded new team, the legendary lineup soon be known as the “Wrecking Crew.” In the August 28th issue of Motorcycle Illustrated America welcomed back one of its most beloved racers from the war to end all wars; “Take your hats and chuck them in the air. Here comes Otto Walker back from Over There.” Walker debuted his new war trophy helmet on September 1st at at the International Championship Road Race in Marion, Indiana, and again a few days later at the new Lakewood Speedway in Atlanta. In this photograph, Walker poses in his new signature helmet and full Harley-Davidson regalia during the week long national races at Ascot Park in January, 1920. Though at the time some would refer to it as bad luck to wear a German’s helmet after the war, its distinct, padded-leather crest separated Walker from the pack and became somewhat of a trademark, the calling card of an American icon.

It is a remarkable event when a photograph captures the very spirit of an individual, forever making that person a friendly acquaintance to anyone fortunate enough to come across his likeness. Meet Morty Graves, one of America’s fastest sons; a legendary pioneer in the sport of motorcycle racing.

Morton James Graves, sometimes referred to as “Millionaire Morty,” was born in Chicago on December 10th, 1890. Morty spent his early years in Chicago, but by 1900 his family had relocated to the Pasadena area just outside of Los Angeles, the womb American motorcycle racing. Like many teenagers of the time, Morty became fascinated with the rapidly developing motorcycle culture in the United States. Living in LA that interest was greatly amplified and it was only a matter of time before a young man’s enthusiasm led him to test his skills on the track. It is said that Morty acquired his first machine, an Indian in 1906 at the age of 16, and within a year he was already on the track and honing his skills in the saddle.

Throughout 1908 Graves raced his Indian on the horse tracks, velodromes, and dirt ovals of California, he also began making appearances outside of the state reaching as far out as Boston. Young Morty lined up against the fathers of American motorcycle racing, competing against Paul Derkum, Charlie Balke, Ray Seymour, Arthur Mitchell, and America's first star Jake DeRosier. His reputation caught the attention of the manufacturers, who were quickly becoming aware of how valuable track presence was becoming and Morty began testing new machines for various companies. In March of 1909 he began a relationship with the German manufacturer NSU, debuting his new ride at the newly constructed Los Angeles Coliseum, America’s first motorcycle board track.

It was at that time that a wonderstruck America witnessed the birth of the Motordrome. Famed bicycle track builder Jack Prince had recently observed the success of his latest experiment, the Clifton Velodrome in Paterson, NJ, a slightly larger version of his typical wooden velodrome design. Onboard a prototype loop-framed Indian, Jake DeRosier smashed nearly every available record of the day on the boards at Clifton and Prince quickly took note. Jack Prince then traveled to LA to build a larger version of the board track, this time the design was tailored specifically for motorcycle racing. It was there that Graves debuted the powerful, belt-driven NSU in March, but by May Morty was back onboard an Indian. In an ironic twist of fate, Morty rocketed into the national spotlight on the boards in LA when, in a brief protest to compete by DeRosier, Graves took the prototype “Bent Tank” Indian that DeRosier had established his own legendary reputation on at Clifton the year before and smashed DeRosier’s 100 mile record by an astonishing 10 minutes.

The dapper teenager, seemingly always with a devilish smile on his face continued to be one of the favored racers, and as the motordrome craze swept through American cities, Graves was a contracted competitor at nearly every opening. In July of 1910 at the Wandamere Motordrome in Salt Lake City, Graves thrilled the crowd when he hoped onboard F.E. Whittler’s Flying Merkel to set a 2-mile record. The brass at Merkel must have liked what they saw, the next month Graves won his first FAM National in Philadelphia onboard a Flying Merkel.

As new motordromes opened their gates throughout the teens, Graves was sure to be there giving veteran racers, local heroes, and eager amateurs a true run for their money. NSU, Flying Merkel, Excelsior, and Indian; no matter the mount Morty was the fastest on the boards in Atlanta, LA, Chicago, Oakland, and Salt Lake City amongst others. In what was reported by Motorcycle Illustrated as “one of the most thrilling track duels that ever happened,” Graves beat out Indian teammate Ray Creviston and rival Dave Kinnie on the mighty yellow Cyclone to win the 100-mile national in Detroit of 1915.

Not to be outpaced on any surface, Graves was just as good in the dirt as he was on the boards, it is where he cut his teeth after all. In fact, at the 1915 Dodge City 300, what many consider to be the debut of Harley-Davidson’s domination on the track, it was Morty Graves who was leading the race until running out of fuel on the last lap due to a crack in his Indian’s tank. Morty continued to compete throughout 1915 and into 1916, though he was burdened with a slew of mechanical difficulties. In a followup performance at the 1916 Dodge City 300 he placed 6th, after being one of the fastest men in the world for nearly a decade he was now being outpaced by a new, hungry, and damn fast generation. Reports from the 1916 Dodge City race are the last to include the legendary “Millionaire" Morty Graves, though in June of 1917 he listed “Motorcycle Racer” as his occupation on his draft card.

Like so many motorcycle racers in the teens, Morty enlisted for service after the interruption of professional racing due to WWI. In July of 1918 he became Private in the US Army through the S.A.T.C. program and was honorably discharged in December. Also in 1918 the 27 year old Graves and his wife Madge welcomed a daughter, Betty Erma that August. When professional motorcycle racing resumed in 1919, Graves, one of the founders of American motorcycle racing had officially retired. After putting away his jersey and helmet Morty went on to open an Indian dealership on Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood where he worked until his death on December 31st, 1944. Eighty-two years after Morty’s last blast around a track he was honored as one of the first inductees into the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 1998.

Seen here with his signature smile, Morty stands with a brawney Big-Base, 8-Valve Indian in front of the 56 degree board track of the Atlanta Motordrome in 1914.