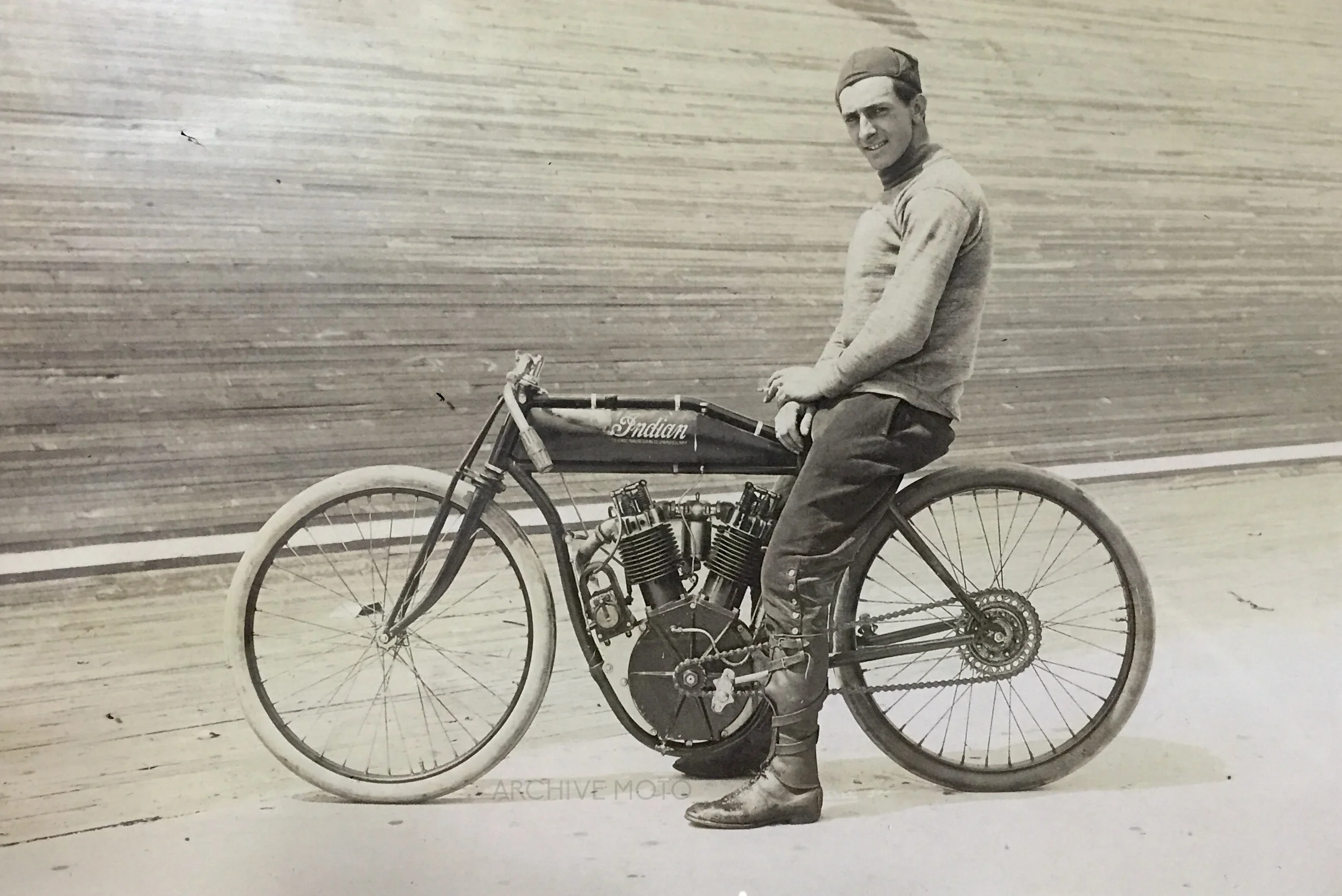

One of motorcycling culture's first ambassadors, here is New Orleans native, pioneer motorcycle racer, and F.A.M. official Arthur Mitchell posing in downtown Birmingham, AL. ca 1912. Mitchell began racing bicycles as a teenager in the late 1800's, and like many of his generation he found himself perfectly positioned to transition into Southern California's motorcycle racing scene as the sport was first taking shape. Mitchell entered his first races in the New Orleans area in 1905, and by 1908 he turned pro. Despite having started out his career on an Indian, Mitchell inked a deal with the German manufacturer NSU in October of 1908 and instantly became the rival for Indian's growing stable. Paul Derkum, Morty Graves, Robert Stubbs, and Jake DeRosier all found Mitchell and his NSU a difficult pair to overcome. Though Mitchell enjoyed a fruitful career with NSU, he raced several different mounts throughout his career including Thor, MM, and Flying Merkel, he even took one of Harley's early development 11K racers out in 1914.

As the sport developed events once held on fairground horse tracks began taking place on the perilous board track motordromes, Mitchell kept his pace and continued to be a fierce competitor. According to an article from the Los Angeles Herald in 1909 Mitchell had the "all of the appearance of a bulldog and the grit of a man who knows no fear." Mitchell's career took him to every corner of the country and as a result of his travels Mitchell was able to interact with many local clubs. Many of these local organizations, especially those located in the southeastern US credit Mitchell as the man who helped their formation. By 1912 he had involved himself with all aspects of the racing game including working as a sanctioned referee for the FAM. Apart from his career as a racer, referee, and FAM representative, Mitchell also held a job as the sales manager for the Texas motorcycle Company in Dallas, TX. in 1911. By the teens Mitchell was heavily involved in the culture of motorcycling in America, and though he was in his 30's the bulldog continued to race.

This photo, taken by Birmingham's moto-enthusiast photographer O.V. Hunt shows Mitchell in downtown Birmingham, AL ca. 1912. Between 1910 and 1913 Mitchell competed in several races in the Magic City onboard Flying Merkels including this iconic twin.

Like most of America's earliest professional motorcycle racers, Cleo Francis Pineau was far from average. A native of Albuquerque, NM., it is said that his restless nature led him to drop out of school in the 6th grade, shortly after which he began racing motorcycles. He was a staple member of the Flying Merkel factory racing team, in the company of such greats as Lee Taylor, Ralph DePalma, Charlie Balke, and Maldwyn Jones. On board his trusty Merkel, Pineau crisscrossed the country in the early teens racing at the most prestigious events of the day, including the 300 mile endurance competition held in Savannah in 1913 and 1914.

With the suspension of professional racing during WWI many racers enlisted for service. Not satisfied with just any role in the war Pineau enlisted in the RAF and became a fighter pilot. He earned his title of Ace after his sixth confirmed kill during aerial dogfighting in France. He himself was then shot down in October of 1918 and held captive in a German prisoner camp. Upon his safe release Pineau was decorated with countless medals and the highest honors from England, France, and Belgium, and even received a hand written letter from King George V welcoming his safe return.

After the war Pineau continued his motorcycle racing career, but by the late 1920's he had ventured into the business world by forming the Radiant Steel Products Company which is still in operation to this day. In addition to his steel company, Pineau also established the Williamsport-Lycoming Airport and was accompanied by his friends and American aviation icons Wiley Post and Amelia Earhart during the opening dedication ceremony. In this photo 20 year old C.F. Pineau sits steely-eyed atop his Merkel single during the June 1914 races held in Toledo. Pineau's Flying Merkel teammate Lee Taylor took the checkered flag that day, and a few months later beat him and the rest of the field again at the 1914 Savannah 300, though his victory in Georgia was on board an Indian twin.

By 1919 the world had finally come out of the desolate haze created by the first World War and in America, motorcycle racing experienced an energized rebirth. Though the once countless manufacturers of American motorcycles had atrophied to a small handful, those who had faired well on the track before the war were now the dominant brands. Indian and Excelsior were early powerhouses in the arena of racing, but they were now joined by a sturdy and hungry Harley-Davidson. The machines became engineered for speed, Big Valve Excelsiors, Keystone framed Harleys and Indians, and new power plants like Indian's Powerplus and Harley's 8-valves made the spectacle of racing even more intoxicating. The exhilarating circular motordrome board tracks had almost all been abandoned before the war and races now took place on dirt road courses, or the handful of large board track speedways. The FAM (Federation of American Motorcyclists) who had helped give birth to organized motorcycle racing in this country had diminished and was replaced by a new sanctioning body, the M&ATA (Motorcycle & Allied Trade Association) who would eventually turn into the modern AMA (American Motorcycle Association). A lot of early board track stars who had transitioned from cycle racing had sadly either died or retired, but a new breed of professional had been mentored and took to the sport just as vigorously. Factory teams busted at the seams with talent and they all came out for the September race in Marion. Otto Walker, Joe Wolters, Shrimp Burns, Bob Perry, Leslie Parkhurst, Teddy Carroll, Ray Weishaar, and Maldwyn Jones were just a few of the now legendary men who took to the 5.17 mile Indiana road course that day. Leslie "Red" Parkhurst, a longtime key player on the Harley team took the checkered flag in Marion, followed by his teammates Ralph Hepburn and Otto Walker to close out the podium for the Milwaukee factory. While you watch notice how big everyone's smile seems to be, this was our revival.

Within a single decade of their American introduction, motorcycles had matured at a frenzied pace, quickly evolving from brittle, finicky gadgets to bruiting, highly-specialized machines. A new American industry exploded, public enthusiasm was brimming over, and the world applauded at the rise of an invigorating new sport. By 1909 the board track motordrome, one of the most romanticized facets ofmotorcycle racing culture was born. A natural derivative of the intensely popular Velodrome bicycle racing, the premier sport of the late 19th century, the American motordrome stadium offered attendees a new level of exhilaration, anticipation, and thrilling danger. In the spring of 1909 the Los Angeles Coliseum, America's first motorcycle board track was alive with the menacing pop of open exhaust, and by 1912 nearly a dozen similar tracks had been erected across the the country.

This photo comes from that The Golden Age of motorcycle racing, a time when motorcycles filled the city streets and county roads of America, and a time when families poured into the infields and grandstands of their closest board track motordromes. This was the era that racing itself was defined, a time in which men established for future icons what it took to be fast and what it meant to be a racer. Taken in July of 1912 inside the newly constructed motordrome in Columbus, Ohio this photo captures Indian factory team rider and Detroit native Don Klark onboard a Big-Base Indian 8-Valve. The earliest version of Indian’s 61ci 8-Valve machines, this model with its rigid-frame, large cases, small tank, and direct-drive chain embodies the simplistic elegance and raw power that can only be seen in board track motorcycles from the era. Just as this Big-Base 8-Valve epitomizes the machines of the American board tracks so too does Klark personify what it meant to be a racer in those early days. The dare-devil grin, cigarette in hand, and wearing what could be considered an uniform best suited for an early autumn stroll Klark, like the other racing pioneers was a gentleman of true grit.